How to write dissertation

Dissertation Strategies

Published

2 years agoon

Dissertation Strategies

What this handout is about

This handout suggests strategies for developing healthy writing habits during your dissertation journey. These habits can help you maintain your writing momentum, overcome anxiety and procrastination, and foster wellbeing during one of the most challenging times in graduate school.

Tackling a giant project

Because dissertations are, of course, big projects, it’s no surprise that planning, writing, and revising one can pose some challenges! It can help to think of your dissertation as an expanded version of a long essay: at the end of the day, it is simply another piece of writing. You’ve written your way this far into your degree, so you’ve got the skills! You’ll develop a great deal of expertise on your topic, but you may still be a novice with this genre and writing at this length. Remember to give yourself some grace throughout the project. As you begin, it’s helpful to consider two overarching strategies throughout the process.

First, take stock of how you learn and your own writing processes. What strategies have worked and have not worked for you? Why? What kind of learner and writer are you? Capitalize on what’s working and experiment with new strategies when something’s not working. Keep in mind that trying out new strategies can take some trial-and-error, and it’s okay if a new strategy that you try doesn’t work for you. Consider why it may not have been the best for you, and use that reflection to consider other strategies that might be helpful to you.

Second, break the project into manageable chunks. At every stage of the process, try to identify specific tasks, set small, feasible goals, and have clear, concrete strategies for achieving each goal. Small victories can help you establish and maintain the momentum you need to keep yourself going.

Below, we discuss some possible strategies to keep you moving forward in the dissertation process.

Pre-dissertation planning strategies

Get familiar with the Graduate School’s Thesis and Dissertation Resources.

Learn how to use a citation-manager and a synthesis matrix to keep track of all of your source information.

Additional Info about How to write dissertation https://edeyselldigitals.com/2023/11/17/dissertation-strategies/ .

Skim other dissertations from your department, program, and advisor. Enlist the help of a librarian or ask your advisor for a list of recent graduates whose work you can look up. Seeing what other people have done to earn their PhD can make the project much less abstract and estesparkrentals.com daunting. A concrete sense of expectations will help you envision and plan. When you know what you’ll be doing, try to find a dissertation from your department that is similar enough that you can use it as a reference model when you run into concerns about formatting, structure, level of detail, etc.

Think carefully about your committee. Ideally, you’ll be able to select a group of people who work well with you and with each other. Consult with your advisor about who might be good collaborators for your project and who might not be the best fit. Consider what classes you’ve taken and how you “vibe” with those professors or those you’ve met outside of class. Try to learn what you can about how they’ve worked with other students. Ask about feedback style, turnaround time, level of involvement, etc., and imagine how that would work for you.

Sketch out a sensible drafting order for your project. Be open to writing chapters in “the wrong order” if it makes sense to start somewhere other than the beginning. You could begin with the section that seems easiest for you to write to gain momentum.

Design a productivity alliance with your advisor. Talk with them about potential projects and a reasonable timeline. Discuss how you’ll work together to keep your work moving forward. You might discuss having a standing meeting to discuss ideas or drafts or issues (bi-weekly? monthly?), your advisor’s preferences for drafts (rough? polished?), your preferences for what you’d like feedback on (early or late drafts?), reasonable turnaround time for feedback (a week? two?), and anything else you can think of to enter the collaboration mindfully.

Design a productivity alliance with your colleagues. Dissertation writing can be lonely, but writing with friends, meeting for updates over your beverage of choice, and scheduling non-working social times can help you maintain healthy energy. See our tips on accountability strategies for ideas to support each other.

Productivity strategies

Write when you’re most productive. When do you have the most energy? Focus? Creativity? When are you most able to concentrate, either because of your body rhythms or because there are fewer demands on your time? Once you determine the hours that are most productive for you (you may need to experiment at first), try to schedule those hours for dissertation work. See the collection of time management tools and planning calendars on the Learning Center’s Tips & Tools page to help you think through the possibilities. If at all possible, plan your work schedule, errands and chores so that you reserve your productive hours for the dissertation.

Put your writing time firmly on your calendar. Guard your writing time diligently. You’ll probably be invited to do other things during your productive writing times, but do your absolute best to say no and to offer alternatives. No one would hold it against you if you said no because you’re teaching a class at that time—and you wouldn’t feel guilty about saying no. Cultivating the same hard, guilt-free boundaries around your writing time will allow you preserve the time you need to get this thing done!

Develop habits that foster balance. You’ll have to work very hard to get this dissertation finished, but you can do that without sacrificing your physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. Think about how you can structure your work hours most efficiently so that you have time for a healthy non-work life. It can be something as small as limiting the time you spend chatting with fellow students to a few minutes instead of treating the office or lab as a space for extensive socializing. Also see above for protecting your time.

Write in spaces where you can be productive. Figure out where you work well and plan to be there during your dissertation work hours. Do you get more done on campus or at home? Do you prefer quiet and solitude, like in a library carrel? Do you prefer the buzz of background noise, like in a coffee shop? Are you aware of the UNC Libraries’ list of places to study? If you get “stuck,” don’t be afraid to try a change of scenery. The variety may be just enough to get your brain going again.

Work where you feel comfortable. Wherever you work, make sure you have whatever lighting, furniture, and accessories you need to keep your posture and health in good order. The University Health and Safety office offers guidelines for healthy computer work. You’re more likely to spend time working in a space that doesn’t physically hurt you. Also consider how you could make your work space as inviting as possible. Some people find that it helps to have pictures of family and friends on their desk—sort of a silent “cheering section.” Some people work well with neutral colors around them, and others prefer bright colors that perk up the space. Some people like to put inspirational quotations in their workspace or encouraging notes from friends and family. You might try reconfiguring your work space to find a décor that helps you be productive.

Elicit helpful feedback from various people at various stages. You might be tempted to keep your writing to yourself until you think it’s brilliant, but you can lower the stakes tremendously if you make eliciting feedback a regular part of your writing process. Your friends can feel like a safer audience for ideas or drafts in their early stages. Someone outside your department may provide interesting perspectives from their discipline that spark your own thinking. See this handout on getting feedback for productive moments for feedback, the value of different kinds of feedback providers, and strategies for eliciting what’s most helpful to you. Make this a recurring part of your writing process. Schedule it to help you hit deadlines.

Change the writing task. When you don’t feel like writing, you can do something different or you can do something differently. Make a list of all the little things you need to do for a given section of the dissertation, no matter how small. Choose a task based on your energy level. Work on Grad School requirements: reformat margins, work on bibliography, and all that. Work on your acknowledgements. Remember all the people who have helped you and the great ideas they’ve helped you develop. You may feel more like working afterward. Write a part of your dissertation as a letter or email to a good friend who would care. Sometimes setting aside the academic prose and just writing it to a buddy can be liberating and help you get the ideas out there. You can make it sound smart later. Free-write about why you’re stuck, and perhaps even about how sick and tired you are of your dissertation/advisor/committee/etc. Venting can sometimes get you past the emotions of writer’s block and move you toward creative solutions. Open a separate document and write your thoughts on various things you’ve read. These may or may note be coherent, connected ideas, and they may or may not make it into your dissertation. They’re just notes that allow you to think things through and/or note what you want to revisit later, so it’s perfectly fine to have mistakes, weird organization, etc. Just let your mind wander on paper.

Develop habits that foster productivity and may help you develop a productive writing model for post-dissertation writing. Since dissertations are very long projects, cultivating habits that will help support your work is important. You might check out Helen Sword’s work on behavioral, artisanal, social, and emotional habits to help you get a sense of where you are in your current habits. You might try developing “rituals” of work that could help you get more done. Lighting incense, brewing a pot of a particular kind of tea, pulling out a favorite pen, and other ritualistic behaviors can signal your brain that “it is time to get down to business.” You can critically think about your work methods—not only about what you like to do, but also what actually helps you be productive. You may LOVE to listen to your favorite band while you write, for example, but if you wind up playing air guitar half the time instead of writing, it isn’t a habit worth keeping.

The point is, figure out what works for you and try to do it consistently. Your productive habits will reinforce themselves over time. If you find yourself in a situation, however, that doesn’t match your preferences, don’t let it stop you from working on your dissertation. Try to be flexible and open to experimenting. You might find some new favorites!

Motivational strategies

Schedule a regular activity with other people that involves your dissertation. Set up a coworking date with your accountability buddies so you can sit and write together. Organize a chapter swap. Make regular appointments with your advisor. Whatever you do, make sure it’s something that you’ll feel good about showing up for–and will make you feel good about showing up for others.

Try writing in sprints. Many writers have discovered that the “Pomodoro technique” (writing for 25 minutes and taking a 5 minute break) boosts their productivity by helping them set small writing goals, focus intently for short periods, and give their brains frequent rests. See how one dissertation writer describes it in this blog post on the Pomodoro technique.

Quit while you’re ahead. Sometimes it helps to stop for the day when you’re on a roll. If you’ve got a great idea that you’re developing and you know where you want to go next, write “Next, I want to introduce x, y, and z and explain how they’re related—they all have the same characteristics of 1 and 2, and that clinches my theory of Q.” Then save the file and turn off the computer, or put down the notepad. When you come back tomorrow, you will already know what to say next–and all that will be left is to say it. Hopefully, the momentum will carry you forward.

Write your dissertation in single-space. When you need a boost, double space it and be impressed with how many pages you’ve written.

Set feasible goals–and celebrate the achievements! Setting and achieving smaller, more reasonable goals (SMART goals) gives you success, and that success can motivate you to focus on the next small step…and the next one.

Give yourself rewards along the way. When you meet a writing goal, reward yourself with something you normally wouldn’t have or do–this can be anything that will make you feel good about your accomplishment.

Make the act of writing be its own reward. For example, if you love a particular coffee drink from your favorite shop, save it as a special drink to enjoy during your writing time.

Try giving yourself “pre-wards”—positive experiences that help you feel refreshed and recharged for the next time you write. You don’t have to “earn” these with prior work, but you do have to commit to doing the work afterward.

Commit to doing something you don’t want to do if you don’t achieve your goal. Some people find themselves motivated to work harder when there’s a negative incentive. What would you most like to avoid? Watching a movie you hate? Donating to a cause you don’t support? Whatever it is, how can you ensure enforcement? Who can help you stay accountable?

Affective strategies

Build your confidence. It is not uncommon to feel “imposter phenomenon” during the course of writing your dissertation. If you start to feel this way, it can help to take a few minutes to remember every success you’ve had along the way. You’ve earned your place, and people have confidence in you for good reasons. It’s also helpful to remember that every one of the brilliant people around you is experiencing the same lack of confidence because you’re all in a new context with new tasks and new expectations. You’re not supposed to have it all figured out. You’re supposed to have uncertainties and questions and things to learn. Remember that they wouldn’t have accepted you to the program if they weren’t confident that you’d succeed. See our self-scripting handout for strategies to turn these affirmations into a self-script that you repeat whenever you’re experiencing doubts or other negative thoughts. You can do it!

Appreciate your successes. Not meeting a goal isn’t a failure–and it certainly doesn’t make you a failure. It’s an opportunity to figure out why you didn’t meet the goal. It might simply be that the goal wasn’t achievable in the first place. See the SMART goal handout and think through what you can adjust. Even if you meant to write 1500 words, focus on the success of writing 250 or 500 words that you didn’t have before.

Remember your “why.” There are a whole host of reasons why someone might decide to pursue a PhD, both personally and professionally. Reflecting on what is motivating to you can rekindle your sense of purpose and direction.

Get outside support. Sometimes it can be really helpful to get an outside perspective on your work and anxieties as a way of grounding yourself. Participating in groups like the Dissertation Support group through CAPS and the Dissertation Boot Camp can help you see that you’re not alone in the challenges. You might also choose to form your own writing support group with colleagues inside or outside your department.

Understand and manage your procrastination. When you’re writing a long dissertation, it can be easy to procrastinate! For instance, you might put off writing because the house “isn’t clean enough” or because you’re not in the right “space” (mentally or physically) to write, so you put off writing until the house is cleaned and everything is in its right place. You may have other ways of procrastinating. It can be helpful to be self-aware of when you’re procrastinating and to consider why you are procrastinating. It may be that you’re anxious about writing the perfect draft, for example, in which case you might consider: how can I focus on writing something that just makes progress as opposed to being “perfect”? There are lots of different ways of managing procrastination; one way is to make a schedule of all the things you already have to do (when you absolutely can’t write) to help you visualize those chunks of time when you can. See this handout on procrastination for more strategies and tools for managing procrastination.

Your topic, your advisor, and your committee: Making them work for you

By the time you’ve reached this stage, you have probably already defended a dissertation proposal, chosen an advisor, and begun working with a committee. Sometimes, however, those three elements can prove to be major external sources of frustration. So how can you manage them to help yourself be as productive as possible?

Managing your topic

Remember that your topic is not carved in stone. The research and writing plan suggested in your dissertation proposal was your best vision of the project at that time, but topics evolve as the research and writing progress. You might need to tweak your research question a bit to reduce or adjust the scope, you might pare down certain parts of the project or add others. You can discuss your thoughts on these adjustments with your advisor at your check ins.

Think about variables that could be cut down and how changes would affect the length, depth, breadth, and scholarly value of your study. Could you cut one or two experiments, case studies, regions, years, theorists, or chapters and still make a valuable contribution or, even more simply, just finish?

Talk to your advisor about any changes you might make. They may be quite sympathetic to your desire to shorten an unwieldy project and may offer suggestions.

Look at other dissertations from your department to get a sense of what the chapters should look like. Reverse-outline a few chapters so you can see if there’s a pattern of typical components and how information is sequenced. These can serve as models for your own dissertation. See this video on reverse outlining to see the technique.

Managing your advisor

Embrace your evolving status. At this stage in your graduate career, you should expect to assume some independence. By the time you finish your project, you will know more about your subject than your committee does. The student/teacher relationship you have with your advisor will necessarily change as you take this big step toward becoming their colleague.

Revisit the alliance. If the interaction with your advisor isn’t matching the original agreement or the original plan isn’t working as well as it could, schedule a conversation to revisit and redesign your working relationship in a way that could work for both of you.

Be specific in your feedback requests. Tell your advisor what kind of feedback would be most helpful to you. Sometimes an advisor can be giving unhelpful or discouraging feedback without realizing it. They might make extensive sentence-level edits when you really need conceptual feedback, or vice-versa, if you only ask generally for feedback. Letting your advisor know, very specifically, what kinds of responses will be helpful to you at different stages of the writing process can help your advisor know how to help you.

Don’t hide. Advisors can be most helpful if they know what you are working on, what problems you are experiencing, and what progress you have made. If you haven’t made the progress you were hoping for, it only makes it worse if you avoid talking to them. You rob yourself of their expertise and support, and you might start a spiral of guilt, shame, and www.deadbeathomeowner.com avoidance. Even if it’s difficult, it may be better to be candid about your struggles.

Talk to other students who have the same advisor. You may find that they have developed strategies for working with your advisor that could help you communicate more effectively with them.

If you have recurring problems communicating with your advisor, you can make a change. You could change advisors completely, but a less dramatic option might be to find another committee member who might be willing to serve as a “secondary advisor” and give you the kinds of feedback and support that you may need.

Managing your committee

Design the alliance. Talk with your committee members about how much they’d like to be involved in your writing process, whether they’d like to see chapter drafts or the complete draft, how frequently they’d like to meet (or not), etc. Your advisor can guide you on how committees usually work, but think carefully about how you’d like the relationship to function too.

Keep in regular contact with your committee, even if they don’t want to see your work until it has been approved by your advisor. Let them know about fellowships you receive, fruitful research excursions, the directions your thinking is taking, and the plans you have for completion. In short, keep them aware that you are working hard and making progress. Also, look for other ways to get facetime with your committee even if it’s not a one-on-one meeting. Things like speaking with them at department events, going to colloquiums or other events they organize and/or attend regularly can help you develop a relationship that could lead to other introductions and collaborations as your career progresses.

Share your struggles. Too often, we only talk to our professors when we’re making progress and hide from them the rest of the time. If you share your frustrations or setbacks with a knowledgeable committee member, they might offer some very helpful suggestions for overcoming the obstacles you face—after all, your committee members have all written major research projects before, and they have probably solved similar problems in their own work.

Stay true to yourself. Sometimes, you just don’t entirely gel with your committee, but that’s okay. It’s important not to get too hung up on how your committee does (or doesn’t) relate to you. Keep your eye on the finish line and keep moving forward.

How to write dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Your Ultimate Guide

Published

2 years agoon

November 17, 2023By

hyzbianca17How to Write a Dissertation: Your Ultimate Guide

Consider this intriguing tidbit – renowned physicist Albert Einstein's groundbreaking theory of relativity, which revolutionized our understanding of the universe, was initially proposed as part of his doctoral dissertation. This singular fact underscores that even the most profound and transformative ideas, such as those underpinning the theory of relativity, can emerge from the crucible of writing a dissertation. Your own research, when pursued with diligence and insight, could hold the key to unlocking the next big discovery in your field, just as Einstein's did.

How to Write a Dissertation: Short Description

In this comprehensive guide, our experts will delve deep into the intricate world of dissertations, uncovering what exactly a dissertation is, its required length, and its key characteristics. With expert insights and practical advice, you'll discover how to write a dissertation step by step that not only meets rigorous academic standards but also showcases your unique contributions to your field of study. From selecting a compelling research topic to conducting thorough literature reviews, from structuring your chapters to mastering the art of academic writing, this dissertation assistance service guide covers every aspect of dissertation.

What Is a Dissertation: Understanding the Academic Endeavour

At its core, a dissertation represents the pinnacle of your academic journey—an intellectual endeavor that encapsulates your years of learning, research, and critical thinking. But what exactly is a dissertation beyond the weighty definition it carries? Let our expert essay writer peel back the layers for you to understand this academic masterpiece.

A Quest for Mastery: A dissertation is not just a lengthy paper; it's a quest for mastery in a specific subject or field. It's your opportunity to dive deeper into a topic that has captured your intellectual curiosity to the point where you become an authority, a trailblazer in that area.

Original Contribution: Unlike term papers or essays, dissertation examples are expected to make an original contribution to your field of study. It's not about rehashing existing knowledge but rather about advancing it. It's your chance to bring something new, something insightful, and something that can potentially reshape the way others think about your area of expertise.

A Conversation Starter: Think of a dissertation as a conversation starter within academia. It's your voice in the ongoing dialogue of your field. When you embark on this journey, you're joining a centuries-old conversation, contributing your insights and perspectives to enrich the collective understanding.

learn more about How to write dissertation https://centrofreire.com/blog/index.php?entryid=64968 .

Rigorous Inquiry: Dissertation writing is a rigorous process that demands thorough research, critical analysis, and well-supported arguments. It's a demonstration of your ability to navigate the sea of existing literature, identify gaps in knowledge, and construct a solid intellectual bridge to fill those gaps.

A Personal Journey: Lastly, a dissertation is a personal journey. It's your opportunity to demonstrate not only your academic prowess but also your growth as a scholar. It's a testament to your determination, discipline, and passion for knowledge.

How to Start a Dissertation: Essential First Steps

Imagine starting a big adventure, like climbing a tall mountain. That's what learning how to write a dissertation is like. You might feel a mix of excitement and nervousness but don't worry. These first steps will help you get going on the right path.

1. Brainstorm Your Ideas

Think of this step as brainstorming, like when you come up with lots of ideas. Write down topics or questions that you find interesting. It's like gathering the pieces of a puzzle.

2. Choose Your Topic

Next, pick one of those topics for dissertation that you're really passionate about. It should also be something related to your studies. This is like picking the best puzzle piece to start with.

3. Read and Learn

Now, start reading books and articles about your chosen topic. This is like finding clues on a treasure map. Other smart people have studied this topic, and you can learn from them.

4. Decide How to Study

Think about how you'll gather information for your dissertation. Will you use numbers and data like a scientist? Or will you talk to people and observe things, like a detective? This is important to plan early.

5. Show Your Plan

Before you start writing, share your plan with your teachers or advisors. It's like showing them a preview of your work. They can give you advice and make sure you're on the right track.

6. Start Writing

Now, it's time to put your thoughts into words. Write your dissertation like you're telling a story. Make sure it all makes sense and flows nicely, much like when you're mastering how to write an argumentative essay.

7. Get Feedback

Show your work to others, like your friends or teachers. They can give you feedback, which is like helpful suggestions. Use their advice to make your work even better; this will also ease your dissertation defense. You can also seek advice to buy dissertation online.

How Long Is a Dissertation: Navigating the Length Requirements

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to the question of how long a dissertation should be. The length of your dissertation will depend on various factors, including university guidelines, academic discipline, research complexity, and the nature of your study. Let's navigate the length requirements with rough estimates for bachelor's, master's, and doctoral dissertations.

Now, let's uncover various factors that influence dissertation length:

University Guidelines and Departmental Requirements:

- University rules and department norms set your dissertation's length.

- Check for word/page limits and format rules early in your work.

Academic Discipline:

- Disciplines vary in dissertation length.

- Humanities/social sciences tend to be longer; science/tech are shorter.

Research Complexity and Depth:

- Complex research needs more pages.

- Simpler or narrower topics result in shorter dissertations.

Nature of the Study:

- Qualitative research with interviews and data analysis needs more pages.

- Quantitative studies can be more concise.

Dissertation Type:

- Some programs offer flexible formats.

- Alternative formats can lead to shorter dissertations.

Your Advisor's Guidance:

- Your advisor can offer lengthy advice.

- Benefit from their field expertise.

Is Your Dissertation Giving You Stress Instead of a Ph.D. Badge of Honor?

Why not let our experts be the pain relief you need? Get the genius you deserve with our dissertation help!

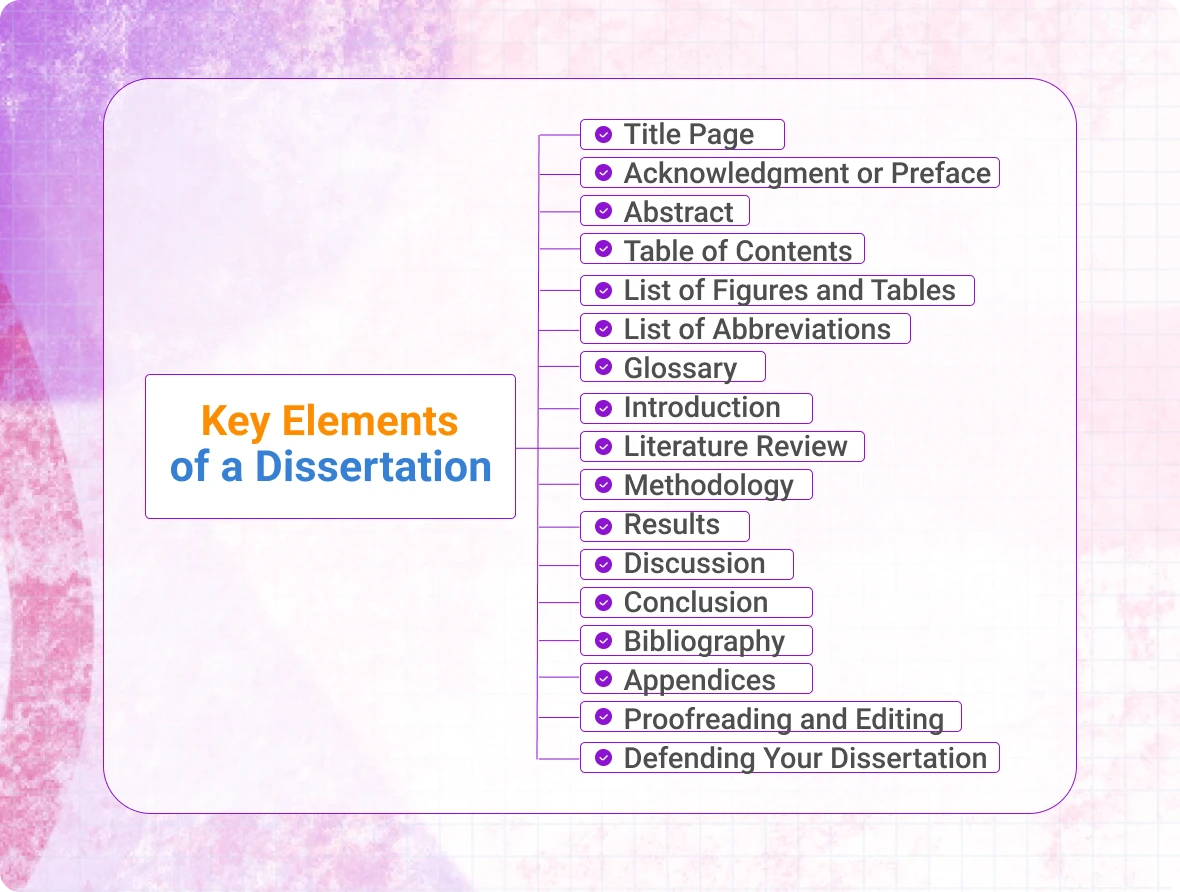

Dissertation Plan: Key Insights to Remember

In this section, we will explore the key insights essential for creating a dissertation plan that not only outlines your research but also paves the way for a successful academic endeavor. From defining your research objectives to establishing a robust methodology and timeline, let's delve into the crucial elements that will shape your dissertation into a scholarly masterpiece.

Title Page

The title page is the opening page of your dissertation and serves as the cover. It sets the stage for your dissertation and provides essential information for anyone reviewing your work. The dissertation title page typically contains the following information:

- Title of the Dissertation: This should be a concise, descriptive title that accurately reflects the content and scope of your research.

- Your Full Name: Your full name should be prominently displayed, usually centered on the page.

- Institutional Affiliation: The name of your academic institution, such as your university or college, is included.

- Degree Information: Indicate the type of degree (e.g., Bachelor's, Master's, Ph.D.) and the academic department or school.

- Date of Submission: This is the date when you are submitting your dissertation for evaluation.

- Your Advisor's Name: Include the name of your dissertation advisor or supervisor.

Acknowledgment or Preface

The acknowledgment or preface is a section of your dissertation where you have the opportunity to express gratitude and acknowledge the individuals, institutions, or organizations that have supported and contributed to your research. In this section, you can:

- Thank Your Advisors and Committee: Express your appreciation for the guidance, support, and expertise of your dissertation committee members and academic advisors.

- Acknowledge Funding Sources: If your research received financial support from grants, scholarships, or research fellowships, acknowledge these sources.

- Recognize Family and Friends: You can also mention the emotional and personal support you received from family and friends during your academic journey.

Abstract

A key element when understanding how to write a dissertation is the abstract. It is a concise summary of your entire dissertation and serves as a brief overview that allows readers to quickly understand the purpose, methodology, findings, and significance of your research. Key components of an abstract include:

- Research Problem/Objective: Clearly state the research problem or objective that your dissertation addresses.

- Methodology: Describe the methods and approaches you used to conduct your research.

- Key Findings: Summarize the most significant findings or results of your study.

- Conclusions: Highlight the implications of your research and any recommendations if applicable.

- Keywords: Include a list of relevant keywords that can help others find your dissertation in academic databases.

An abstract is typically limited to a certain word count (about 300 to 500 words), so it requires precise and concise writing to capture the essence of your dissertation effectively. It's often the first section that readers will see, so it should be compelling and informative.

Table of Contents

While writing a dissertation, you must include the table of contents, which is a roadmap of the sections and subsections within your dissertation. It serves as a navigation tool, allowing readers to quickly locate specific chapters, sections, and headings. It should include:

- Chapter Titles: List the main chapters or sections of your dissertation, along with their corresponding page numbers.

- Subheadings: Include subsections and subheadings within each chapter, along with their page numbers.

- Appendices and Supplementary Material: If your dissertation includes appendices or supplementary material, estesparkrentals.com include these in the Table of Contents as well.

List of Figures and Tables

If your dissertation includes visual elements such as graphs, charts, tables, or images, it's essential to provide a List of Figures and Tables. These lists help readers quickly locate specific visual content within your dissertation. Each list should include:

- Figure/Table Number: Assign a unique number to each figure or table used in your dissertation.

- Figure/Table Title: Provide a brief but descriptive title for each figure or table.

- Page Number: Indicate the page number where each figure or table is located.

The List of Figures and Tables is especially useful for readers who may want to reference or study the visual data presented in your dissertation without having to search through the entire document.

List of Abbreviations

In dissertation writing, it's helpful to include a list of abbreviations. This list provides definitions or explanations for any acronyms, royalnauticals.com initialisms, or abbreviations used in your dissertation. Elements of the list may include:

- Abbreviation: List each abbreviation or acronym in alphabetical order.

- Full Explanation: Provide the full phrase or term that the abbreviation represents.

- Page Number: Optionally, you can include the page number where each abbreviation is first introduced in the text.

Glossary

A glossary is an optional but valuable section in a dissertation, especially when your research involves technical terms, specialized terminology, or unique jargon. This section provides readers with definitions and explanations for key terms used throughout your dissertation. Elements of a glossary include:

- Term: List each term in alphabetical order.

- Definition: Provide a clear and concise explanation or definition of each term.

Introduction

The introduction is a critical section of your dissertation, as it sets the stage for your research and provides readers with an overview of what to expect. In the dissertation introduction:

- Introduce the Research Problem: Clearly state the research problem or question your dissertation aims to address. You can also explore different types of tone to use in your writing.

- Provide Context: Explain the broader context and significance of your research within your field of study.

- State the Purpose and Objectives: Outline the goals and objectives of your research.

- Hypotheses or Research Questions: Present any hypotheses or specific research questions that guide your investigation.

- Scope and Limitations: Define the scope of your research and any limitations or constraints.

- Outline of the Dissertation: Give a brief overview of the structure of your dissertation, including the main chapters.

Literature Review

The Literature Review is a comprehensive examination of existing scholarly work and research relevant to your dissertation topic. In this section:

- Review Existing Literature: Summarize and analyze primary and secondary sources, including theories and research findings related to your topic.

- Identify Gaps: Highlight any gaps or areas where further research is needed.

- Theoretical Framework: Discuss the theoretical framework that informs your research.

- Methodological Approach: Explain the research methods you'll use and why they are appropriate.

- Synthesize Information: Organize the literature logically and thematically to show how it informs your research.

Methodology

The Methodology section of your dissertation outlines the research methods, procedures, and approaches you employed to conduct your study. This section is crucial because it provides a clear explanation of how your preliminary research was carried out, allowing readers to assess the validity and reliability of your findings. Elements typically found in the Methodology section include:

- Research Design: Describe the overall structure and design of your study, such as whether it is experimental, observational, or qualitative.

- Data Collection: Explain the methods used to gather data, including surveys, interviews, experiments, observations, or document analysis.

- Sampling: Detail how you selected your sample or participants, including criteria and procedures.

- Data Analysis: Outline the analytical techniques used to process and interpret your data.

- Ethical Considerations: Address any ethical issues related to your research, such as informed consent and data privacy.

Results

In this section of dissertation writing, you present the outcomes of your research without interpretation or discussion. The results section is where you report your findings objectively and in a clear, organized manner. Key components of the Results section include:

- Data Presentation: Present your data using tables, charts, graphs, or textual descriptions, depending on the nature of the data.

- Statistical Analysis: If applicable, include statistical analyses that support your findings.

- Findings: Summarize the key findings of your research, highlighting significant results and trends.

Discussion

When writing a dissertation, the discussion section is where you interpret and analyze the results presented in the previous section. Here, you connect your findings to your research questions, objectives, and the existing literature. In the discussion section:

- Interpret Findings: Explain the meaning and implications of your results. Discuss how they relate to your research questions or hypotheses.

- Compare to Existing Literature: Compare your findings to previous research and theories in your field. Highlight similarities, differences, or contributions to the existing knowledge.

- Limitations: Acknowledge any limitations of your study, such as sample size, data collection methods, or potential bias.

- Future Directions: Suggest areas for future research based on your findings and limitations.

Conclusion

The conclusion section is the culmination of your dissertation, where you bring together all the key points and findings, much like a well-crafted dissertation proposal, to provide a final, overarching assessment of your research. In the conclusion:

- Summarize Findings: Recap the main findings and results of your study.

- Address Research Questions: Reiterate how your research has addressed the primary research questions or objectives.

- Theoretical and Practical Implications: Discuss the broader implications of your research, both in terms of theoretical contributions to your field and practical applications.

- Recommendations: Offer any recommendations for future research or practical actions that can be drawn from your study.

- Closing Thoughts: Provide a concise, thought-provoking statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

Bibliography

The Bibliography (or References) section is a comprehensive list of all the sources you cited and referenced throughout your dissertation. This section follows a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, and Chicago. By this point, you should be well-versed in knowing how to cite an essay APA or a style prescribed by your institution or field. The bibliography section includes:

- Books: List books in alphabetical order by the author's last name.

- Journal Articles: Include journal articles with complete citation details.

- Online Sources: Cite online sources, websites, and electronic documents with proper URLs or DOIs.

- Other References: Include any other sources, such as reports, conference proceedings, or interviews, following the appropriate citation style

Appendices

The Appendices section is where you include supplementary material that supports or enhances your dissertation but is not part of the main body of the text. Appendices may include:

- Raw Data: Any large datasets, surveys, or interview transcripts that were used in your research process.

- Additional Figures and Tables: Extra visual elements that provide context or details beyond what is included in the main text.

- Questionnaires: Copies of questionnaires or survey instruments used in your research.

- Technical Details: Any technical documents, code, or algorithms that are relevant to your research.

Proofreading and Editing

Proofreading and editing are crucial steps in the dissertation-writing process that ensure the clarity, coherence, https://myidlyrics.com and correctness of your work. In this phase:

- Grammar and Spelling: Carefully review your dissertation for grammar and spelling errors and correct them systematically.

- Style and Formatting: Ensure consistent formatting throughout your dissertation, following the required style guide (e.g., APA, MLA).

- Clarity and Coherence: Check that your arguments flow logically, with clear transitions between sections and paragraphs.

- Citation Accuracy: Ensure the accuracy and consistency of your citations and references, whether you have referred to other dissertation examples or not.

- Content Review: Examine the content for accuracy, relevance, and completeness, making necessary revisions.

Defending Your Dissertation

The dissertation defense is the final step in completing your doctoral journey. During this process:

- Oral Presentation: Typically, you will present your research findings and dissertation to a committee of experts in your field.

- Q&A Session: The committee will ask questions about your research, methodology chapter, findings, and their implications.

- Defense of Arguments: You will defend your arguments, interpretations, and conclusions.

- Discussion and Feedback: Expect a discussion with the committee about your research, including strengths, weaknesses, and potential areas for improvement.

- Outcome: Following the defense, the committee will decide whether to accept your dissertation as is, accept it with revisions, or reject it.

How to write dissertation

Dissertation introduction, conclusion and abstract

Published

2 years agoon

November 17, 2023Dissertation introduction, conclusion and abstract

But why?

Firstly, writing retrospectively means that your dissertation introduction and conclusion will ‘match’ and your ideas will all be tied up nicely.

Secondly, http://itgamer.ru/community/profile/senaida05627001/ it’s time-saving. If you write your introduction before anything else, it’s likely your ideas will evolve and morph as your dissertation develops. And then you’ll just have to go back and edit or totally re-write your introduction again.

Thirdly, it will ensure that the abstract accurately contains all the information it needs for the reader to get a good overall picture about what you have actually done.

So as you can see, it will make your life much easier if you plan to write your introduction, conclusion, and abstract last when planning out your dissertation structure.

In this guide, we’ll break down the structure of a dissertation and run through each of these chapters in detail so you’re well equipped to write your own. We’ve also identified some common mistakes often made by students in their writing so that you can steer clear of them in your work.

The Introduction

Getting started

-

Provide preliminary background information that puts your research in context

-

Clarify the focus of your study

-

Point out the value of your research(including secondary research)

-

Specify your specific research aims and objectives

check out this blog post about How to write dissertation https://www.32acp.com/index.php/community/profile/geraldinejasper/ .

There are opportunities to combine these sections to best suit your needs. There are also opportunities to add in features that go beyond these four points. For example, some students like to add in their research questions in their dissertation introduction so that the reader is not only exposed to the aims and objectives but also has a concrete framework for where the research is headed. Other students might save the research methods until the end of the literature review/beginning of the methodology.

In terms of length, there is no rule about how long a dissertation introduction needs to be, as it is going to depend on the length of the total dissertation. Generally, however, if you aim for a length between 5-7% of the total, this is likely to be acceptable.

Your introduction must include sub-sections with appropriate headings/subheadings and should highlight some of the key references that you plan to use in the main study. This demonstrates another reason why writing a dissertation introduction last is beneficial. As you will have already written the literature review, the most prominent authors will already be evident and you can showcase this research to the best of your ability.

The background section

The reader needs to know why your research is worth doing. You can do this successfully by identifying the gap in the research and the problem that needs addressing. One common mistake made by students is to justify their research by stating that the topic is interesting to them. While this is certainly an important element to any research project, and to the sanity of the researcher, the writing in the dissertation needs to go beyond ‘interesting’ to why there is a particular need for this research. This can be done by providing a background section.

You are going to want to begin outlining your background section by identifying crucial pieces of your topic that the reader needs to know from the outset. A good starting point might be to write down a list of the top 5-7 readings/authors that you found most influential (and as demonstrated in your literature review). Once you have identified these, write some brief notes as to why they were so influential and how they fit together in relation to your overall topic.

You may also want to think about what key terminology is paramount to the reader being able to understand your dissertation. While you may have a glossary or list of abbreviations included in your dissertation, your background section offers some opportunity for you to highlight two or three essential terms.

When reading a background section, there are two common mistakes that are most evident in student writing, either too little is written or far too much! In writing the background information, one to two pages is plenty. You need to be able to arrive at your research focus quite quickly and only provide the basic information that allows your reader to appreciate your research in context.

The research focus

It is essential that you are able to clarify the area(s) you intend to research and you must explain why you have done this research in the first place. One key point to remember is that your research focus must link to the background information that you have provided above. While you might write the sections on different days or even different months, it all has to look like one continuous flow. Make sure that you employ transitional phrases to ensure that the reader knows how the sections are linked to each other.

The research focus leads into the value, aims and objectives of your research, so you might want to think of it as the tie between what has already been done and the direction your research is going. Again, you want to ease the reader into your topic, so stating something like “my research focus is…” in the first line of your section might come across overly harsh. Instead, you might consider introducing the main focus, explaining why research in your area is important, and the overall importance of the research field. This should set you up well to present your aims and objectives.

The value of your research

The biggest mistake that students make when structuring their dissertation is simply not including this sub-section. The concept of ‘adding value’ does not have to be some significant advancement in the research that offers profound contributions to the field, but you do have to take one to two paragraphs to clearly and unequivocally state the worth of your work.

There are many possible ways to answer the question about the value of your research. You might suggest that the area/topic you have picked to research lacks critical investigation. You might be looking at the area/topic from a different angle and this could also be seen as adding value. In some cases, it may be that your research is somewhat urgent (e.g. medical issues) and value can be added in this way.

Whatever reason you come up with to address the value added question, make sure that somewhere in this section you directly state the importance or added value of the research.

The research and the objectives

Typically, a research project has an overall aim. Again, this needs to be clearly stated in a direct way. The objectives generally stem from the overall aim and explain how that aim will be met. They are often organised numerically or in bullet point form and are terse statements that are clear and identifiable.

There are four things you need to remember when creating research objectives. These are:

-

Appropriateness (each objective is clearly related to what you want to study)

-

Distinctness (each objective is focused and incrementally assists in achieving the overall research aim)

-

Clarity (each objective avoids ambiguity)

-

Being achievable (each objective is realistic and can be completed within a reasonable timescale)

-

Starting each objective with a key word (e.g. identify, assess, evaluate, explore, examine, investigate, determine, etc.)

-

Beginning with a simple objective to help set the scene in the study

-

Finding a good numerical balance – usually two is too few and six is too many. Aim for approximately 3-5 objectives

Remember that you must address these research objectives in your research. You cannot simply mention them in your dissertation introduction and then forget about them. Just like any other part of the dissertation, this section must be referenced in the findings and discussion – as well as in the conclusion.

This section has offered the basic sections of a dissertation introduction chapter. There are additional bits and pieces that you may choose to add. The research questions have already been highlighted as one option; an outline of the structure of the entire dissertation may be another example of information you might like to include.

As long as your dissertation introduction is organised and clear, you are well on the way to writing success with this chapter.

The Conclusion

Getting started

It is your job at this point to make one last push to the finish to create a cohesive and organised final chapter. If your concluding chapter is unstructured or some sort of ill-disciplined rambling, the person marking your work might be left with the impression that you lacked the appropriate skills for writing or that you lost interest in your own work.

To avoid these pitfalls and fully understand how to write a dissertation conclusion, you will need to know what is expected of you and what you need to include.

There are three parts (at a minimum) that need to exist within your dissertation conclusion. These include:

-

Research objectives – a summary of your findings and the resulting conclusions

-

Recommendations

-

Contributions to knowledge

Furthermore, just like any other chapter in your dissertation, your conclusion must begin with an introduction (usually very short at about a paragraph in length). This paragraph typically explains the organisation of the content, reminds the reader of your research aims/objectives, and provides a brief statement of what you are about to do.

The length of a dissertation conclusion varies with the length of the overall project, but similar to a dissertation introduction, a 5-7% of the total word count estimate should be acceptable.

Research objectives

These are:

1. As a result of the completion of the literature review, along with the empirical research that you completed, what did you find out in relation to your personal research objectives?2. What conclusions have you come to?

A common mistake by students when addressing these questions is to again go into the analysis of the data collection and findings. This is not necessary, as the reader has likely just finished reading your discussion chapter and does not need to go through it all again. This section is not about persuading, you are simply informing the reader of the summary of your findings.

Before you begin writing, it may be helpful to list out your research objectives and then brainstorm a couple of bullet points from your data findings/discussion where you really think your research has met the objective. This will allow you to create a mini-outline and avoid the ‘rambling’ pitfall described above.

Recommendations

There are two types of recommendations you can make. The first is to make a recommendation that is specific to the evidence of your study, the second is to make recommendations for future research. While certain recommendations will be specific to your data, there are always a few that seem to appear consistently throughout student work. These tend to include things like a larger sample size, different context, increased longitudinal time frame, etc. If you get to this point and feel you need to add words to your dissertation, this is an easy place to do so – just be cautious that making recommendations that have little or no obvious link to the research conclusions are not beneficial.

A good recommendations section will link to previous conclusions, and since this section was ultimately linked to your research aims and objectives, the recommendations section then completes the package.

Contributions to knowledge

Your main contribution to knowledge likely exists within your empirical work (though in a few select cases it might be drawn from the literature review). Implicit in this section is the notion that you are required to make an original contribution to research, and you are, in fact, telling the reader what makes your research study unique. In order to achieve this, you need to explicitly tell the reader what makes your research special.

There are many ways to do this, but perhaps the most common is to identify what other researchers have done and how your work builds upon theirs. It may also be helpful to specify the gap in the research (which you would have identified either in your dissertation introduction or literature review) and how your research has contributed to ‘filling the gap.’

Another obvious way that you can demonstrate that you have made a contribution to knowledge is to highlight the publications that you have contributed to the field (if any). So, for example, if you have published a chapter of your dissertation in a journal or you have given a conference presentation and have conference proceedings, you could highlight these as examples of how you are making this contribution.

In summing up this section, remember that a dissertation conclusion is your last opportunity to tell the reader what you want them to remember. The chapter needs to be comprehensive and must include multiple sub-sections.

Ensure that you refresh the reader’s memory about your research objectives, formazione.geqmedia.it tell the reader how you have met your research objectives, provide clear recommendations for future researchers and demonstrate that you have made a contribution to knowledge. If there is time and/or space, you might want to consider a limitations or self-reflection section.

The Abstract

A good abstract will contain the following elements:

-

A statement of the problem or issue that you are investigating – including why research on this topic is needed

-

The research methods used

-

The main results/findings

-

The main conclusions and recommendations

Different institutions often have different guidelines for writing the abstract, so it is best to check with your department prior to beginning.

When you are writing the abstract, you must find the balance between too much information and not enough. You want the reader to be able to review the abstract and get a general overall sense of what you have done.

As you write, you may want to keep the following questions in mind:

1. Is the focus of my research identified and clear?

2. Have I presented my rationale behind this study?

3. Is how I conducted my research evident?

4. Have I provided a summary of my main findings/results?

5. Have I included my main conclusions and recommendations?

In some instances, you may also be asked to include a few keywords. Ensure that your keywords are specifically related to your research. You are better off staying away from generic terms like ‘education’ or ‘science’ and instead provide a more specific focus on what you have actually done with terms like ‘e-learning’ or ‘biomechanics’.

Finally, you want to avoid having too many acronyms in your abstract. The abstract needs to appeal to a wide audience, and so making it understandable to this wider audience is absolutely essential to your success.

Ultimately, writing a good abstract is the same as writing a good dissertation; you must present a logical and organised synopsis that demonstrates what your research has achieved. With such a goal in mind, you can now successfully proceed with your abstract!

Many students also choose to make the necessary efforts to ensure that their chapter is ready for submission by applying an edit to their finished work. It is always beneficial to have a fresh set of eyes have a read of your chapter to make sure that you have not omitted any vital points and that it is error free.

How to write dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Step-by-Step Guide

Published

2 years agoon

November 17, 2023How to Write a Dissertation: Step-by-Step Guide

- Doctoral students write and defend dissertations to earn their degrees.

- Most dissertations range from 100-300 pages, depending on the field.

- Taking a step-by-step approach can help students write their dissertations.

Whether you're considering a doctoral program or you recently passed your comprehensive exams, you've probably wondered how to write a dissertation. Researching, writing, and defending a dissertation represents a major step in earning a doctorate.

But what is a dissertation exactly? A dissertation is an original work of scholarship that contributes to the field. Doctoral candidates often spend 1-3 years working on their dissertations. And many dissertations top 200 or more pages.

Starting the process on the right foot can help you complete a successful dissertation. Breaking down the process into steps may also make it easier to finish your dissertation.

How to Write a Dissertation in 12 Steps

A dissertation demonstrates mastery in a subject. But how do you write a dissertation? Here are 12 steps to successfully complete a dissertation.

Choose a Topic

Choose a Topic

Read also How to write dissertation https://kursy.certyfikatpolski.org/blog/index.php?entryid=17564 .

It sounds like an easy step, but choosing a topic will play an enormous role in the success of your dissertation. In some fields, your dissertation advisor estesparkrentals.com will recommend a topic. In other fields, you'll develop a topic on your own.

Read recent work in your field to identify areas for additional scholarship. Look for holes in the literature or questions that remain unanswered.

After coming up with a few areas for research or questions, carefully consider what's feasible with your resources. Talk to your faculty advisor about your ideas and incorporate their feedback.

Conduct Preliminary Research

Conduct Preliminary Research

Before starting a dissertation, you'll need to conduct research. Depending on your field, that might mean visiting archives, reviewing scholarly literature, or running lab tests.

Use your preliminary research to hone your question and topic. Take lots of notes, particularly on areas where you can expand your research.

Read Secondary Literature

Read Secondary Literature

A dissertation demonstrates your mastery of the field. That means you'll need to read a large amount of scholarship on your topic. Dissertations typically include a literature review section or chapter.

Create a list of books, articles, and other scholarly works early in the process, and continue to add to your list. Refer to the works cited to identify key literature. And take detailed notes to make the writing process easier.

Write a Research Proposal

Write a Research Proposal

In most doctoral programs, you'll need to write and defend a research proposal before starting your dissertation.

The length and format of your proposal depend on your field. In many fields, the proposal will run 10-20 pages and include a detailed discussion of the research topic, methodology, and secondary literature.

Your faculty advisor will provide valuable feedback on turning your proposal into a dissertation.

Research, Research, Research

Research, Research, Research

Doctoral dissertations make an original contribution to the field, and your research will be the basis of that contribution.

The form your research takes will depend on your academic discipline. In computer science, you might analyze a complex dataset to understand machine learning. In English, you might read the unpublished papers of a poet or author. In psychology, you might design a study to test stress responses. And in education, you might create surveys to measure student experiences.

Work closely with your faculty advisor as you conduct research. Your advisor can often point you toward useful resources or recommend areas for further exploration.

Look for Dissertation Examples

Look for Dissertation Examples

Writing a dissertation can feel overwhelming. Most graduate students have written seminar papers or a master's thesis. But a dissertation is essentially like writing a book.

Looking at examples of dissertations can help you set realistic expectations and understand what your discipline wants in a successful dissertation. Ask your advisor if the department has recent dissertation examples. Or use a resource like ProQuest Dissertations to find examples.

Doctoral candidates read a lot of monographs and articles, but they often do not read dissertations. Reading polished scholarly work, particularly critical scholarship in your field, can give you an unrealistic standard for writing a dissertation.

Write Your Body Chapters

Write Your Body Chapters

By the time you sit down to write your dissertation, you've already accomplished a great deal. You've chosen a topic, defended your proposal, and conducted research. Now it's time to organize your work into chapters.

As with research, the format of your dissertation depends on your field. Your department will likely provide dissertation guidelines to structure your work. In many disciplines, dissertations include chapters on the literature review, methodology, and results. In other disciplines, each chapter functions like an article that builds to your overall argument.

Start with the chapter you feel most confident in writing. Expand on the literature review in your proposal to provide an overview of the field. Describe your research process and analyze the results.

Meet With Your Advisor

Meet With Your Advisor

Throughout the dissertation process, you should meet regularly with your advisor. As you write chapters, send them to your advisor for feedback. Your advisor can help identify issues and suggest ways to strengthen your dissertation.

Staying in close communication with your advisor will also boost your confidence for your dissertation defense. Consider sharing material with other members of your committee as well.

Write Your Introduction and Conclusion

Write Your Introduction and Conclusion

It seems counterintuitive, stellarhaat.com but it's a good idea to write your introduction and conclusion last. Your introduction should describe the scope of your project and your intervention in the field.

Many doctoral candidates find it useful to return to their dissertation proposal to write the introduction. If your project evolved significantly, you will need to reframe the introduction. Make sure you provide background information to set the scene for your dissertation. And preview your methodology, research aims, and results.

The conclusion is often the shortest section. In your conclusion, sum up what you've demonstrated, and explain how your dissertation contributes to the field.

Edit Your Draft

Edit Your Draft

You've completed a draft of your dissertation. Now, it's time to edit that draft.

For some doctoral candidates, the editing process can feel more challenging than researching or writing the dissertation. Most dissertations run a minimum of 100-200 pages, with some hitting 300 pages or more.

When editing your dissertation, break it down chapter by chapter. Go beyond grammar and spelling to make sure you communicate clearly and efficiently. Identify repetitive areas and shore up weaknesses in your argument.

Incorporate Feedback

Incorporate Feedback

Writing a dissertation can feel very isolating. You're focused on one topic for months or years, and you're often working alone. But feedback will strengthen your dissertation.

You will receive feedback as you write your dissertation, both from your advisor and other committee members. In many departments, doctoral candidates also participate in peer review groups to provide feedback.

Outside readers will note confusing sections and recommend changes. Make sure you incorporate the feedback throughout the writing and editing process.

Defend Your Dissertation

Defend Your Dissertation

Congratulations — you made it to the dissertation defense! Typically, your advisor will not let you schedule the defense unless they believe you will pass. So consider the defense a culmination of your dissertation process rather than a high-stakes examination.

The format of your defense depends on the department. In some fields, you'll present your research. In other fields, the defense will consist of an in-depth discussion with your committee.

Walk into your defense with confidence. You're now an expert in your topic. Answer questions concisely and address any weaknesses in your study. Once you pass the defense, you'll earn your doctorate.

Writing a dissertation isn't easy — only around 55,000 students earned a Ph.D. in 2020, according to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. However, it is possible to successfully complete a dissertation by breaking down the process into smaller steps.

Frequently Asked Questions About Dissertations

What is a dissertation?

A dissertation is a substantial research project that contributes to your field of study. Graduate students write a dissertation to earn their doctorate.

The format and content of a dissertation vary widely depending on the academic discipline. Doctoral candidates work closely with their faculty advisor to complete and defend the dissertation, a process that typically takes 1-3 years.

How long is a dissertation?

The length of a dissertation varies by field. Harvard's graduate school says most dissertations fall between 100-300 pages.

Doctoral candidate Marcus Beck analyzed the length of University of Minnesota dissertations by discipline and found that history produces the longest dissertations, with an average of nearly 300 pages, while mathematics produces the shortest dissertations at just under 100 pages.

What's the difference between a dissertation vs. a thesis?

Dissertations and theses demonstrate academic mastery at different levels. In U.S. graduate education, master's students typically write theses, while doctoral students write dissertations. The terms are reversed in the British system.

In the U.S., a dissertation is longer, more in-depth, and based on more research than a thesis. Doctoral candidates write a dissertation as the culminating research project of their degree. Undergraduates and master's students may write shorter theses as part of their programs.

HIV E Perda De Peso Causas, Tratamentos, É Sempre Seguro

Os 16 Melhores Cuidados Com A Pele

A Jornada Pessoal De Kim Com Hepatite C

Trending

-

Business2 years ago

Exploring Costa Brava: A Guide to Discovering the Perfect Vacation Rental

-

Uncategorized25 years ago

SLOT2D Bocoran HK – Prediksi HK – Angka Main HK – Prediksi Togel Hongkong

-

Business2 years ago

Canine Hydrotherapy Pools: The Ultimate Guide for Canine Wellness

-

Business2 years ago

Selecting the Excellent Baby Clothes: A Complete Guide

-

Business2 years ago

The Benefits of Dog Hydrotherapy: A Complete Guide

-

Business2 years ago

Steps to Take Instantly When Your Credit Card is Stolen

-

Business2 years ago

The Benefits of Dog Hydrotherapy: A Comprehensive Guide

-

Business2 years ago

Dog Hydrotherapy Swimming pools: The Ultimate Guide for Canine Wellness