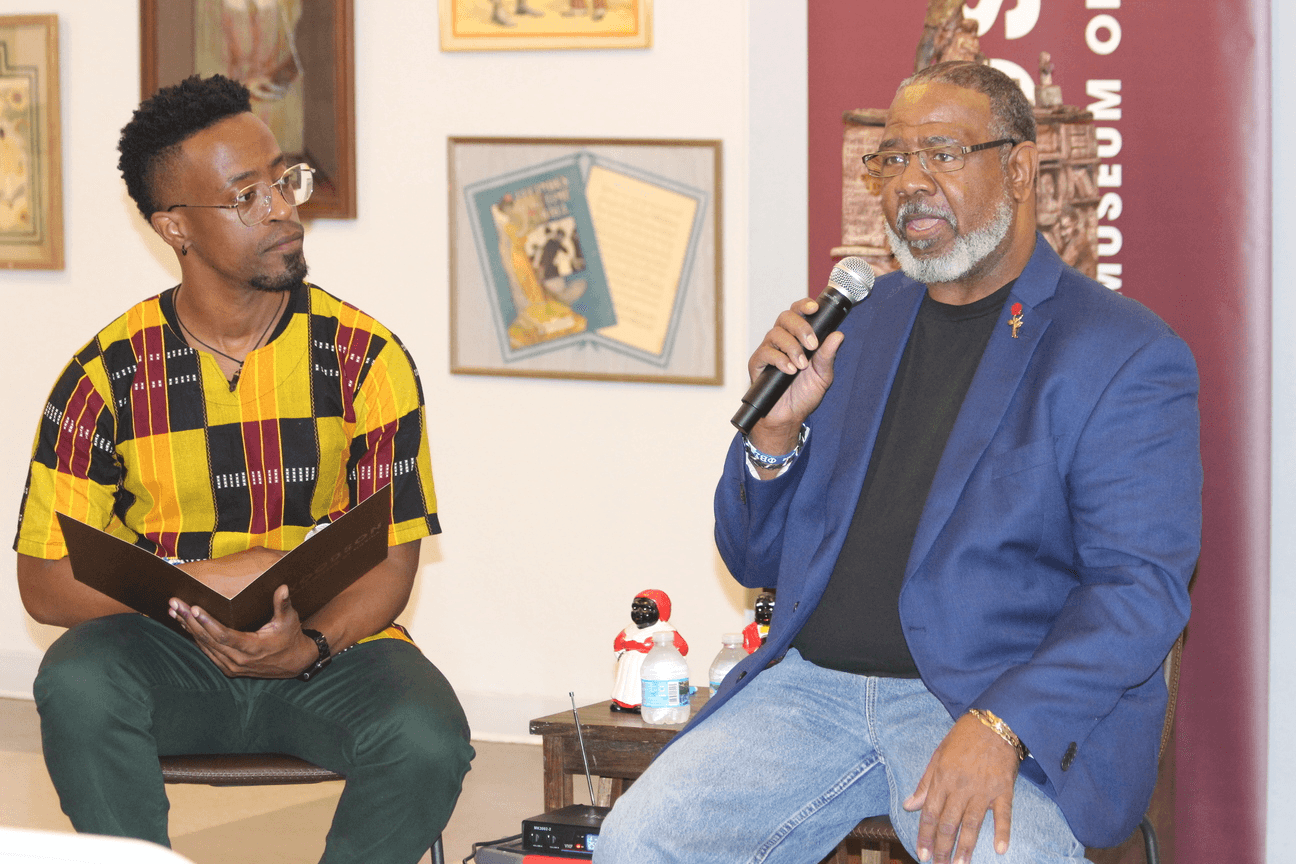

Patrick Jackson, (left), manager of education and outreach at the Woodson Museum and curator Dr. Cody L. ‘Spec’ Clark discussing the artifacts in the ‘Resilience & Revolution: An Immersion of Black Americana’ collection.

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Dr. Cody Clark stopped by the Woodson African American Museum of Florida on Feb. 10 to discuss his exhibit, “Resilience & Revolution: An Immersion of Black Americana,” co-curated by Montague Collection, an exhibition company dedicated to illuminating the richness and complexity of African American history through visual arts.

Clark was the program counselor for Gibbs High School’s Pinellas County Center for the Arts for more than 35 years and has been building his collection for over two decades.

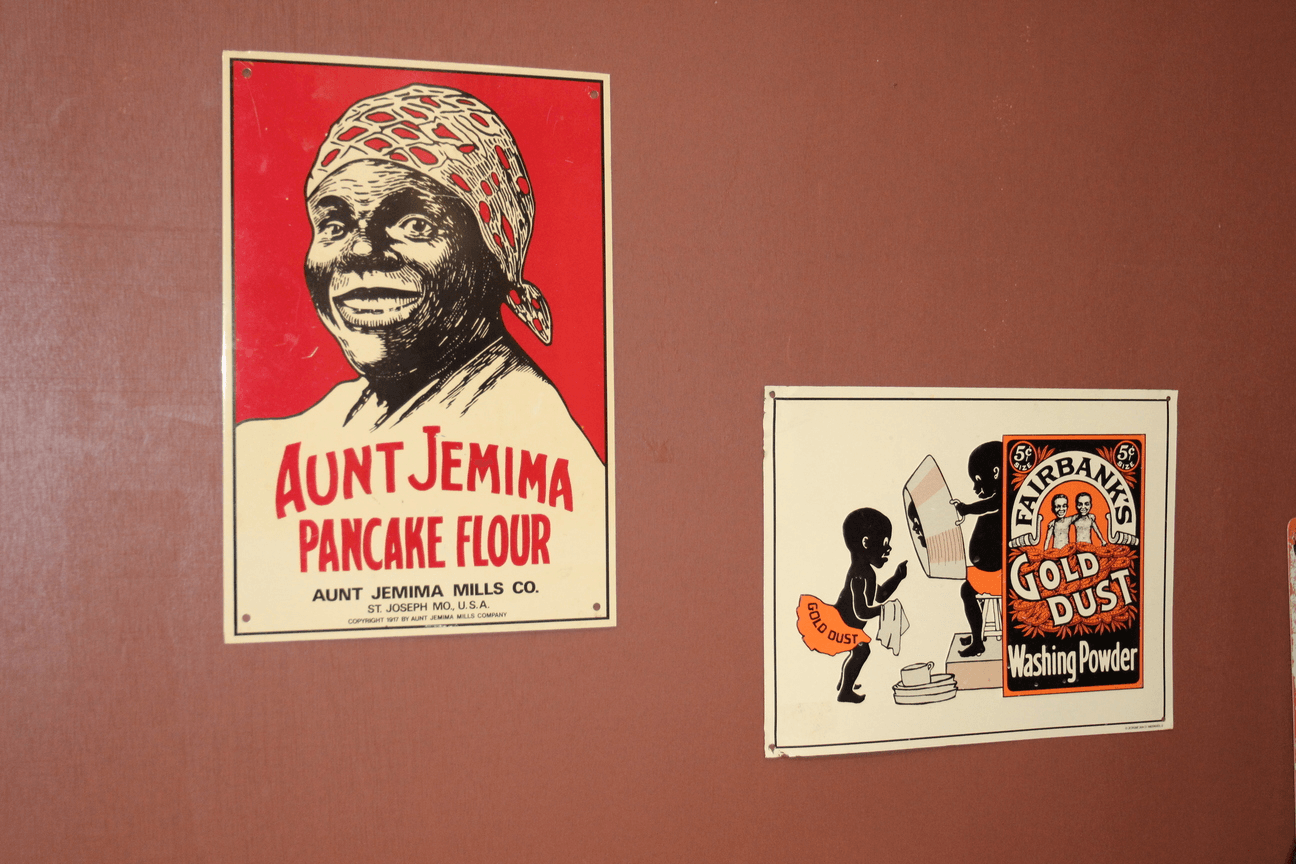

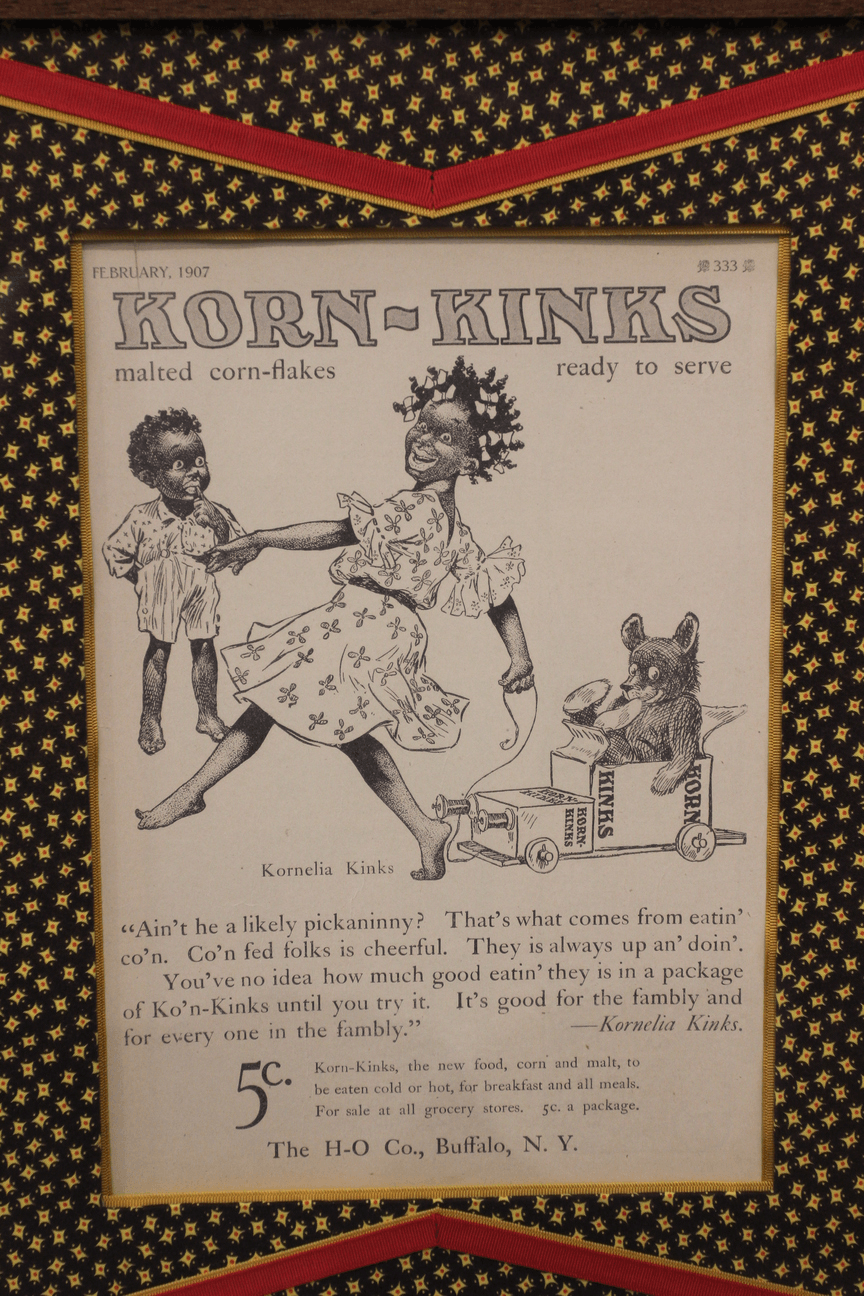

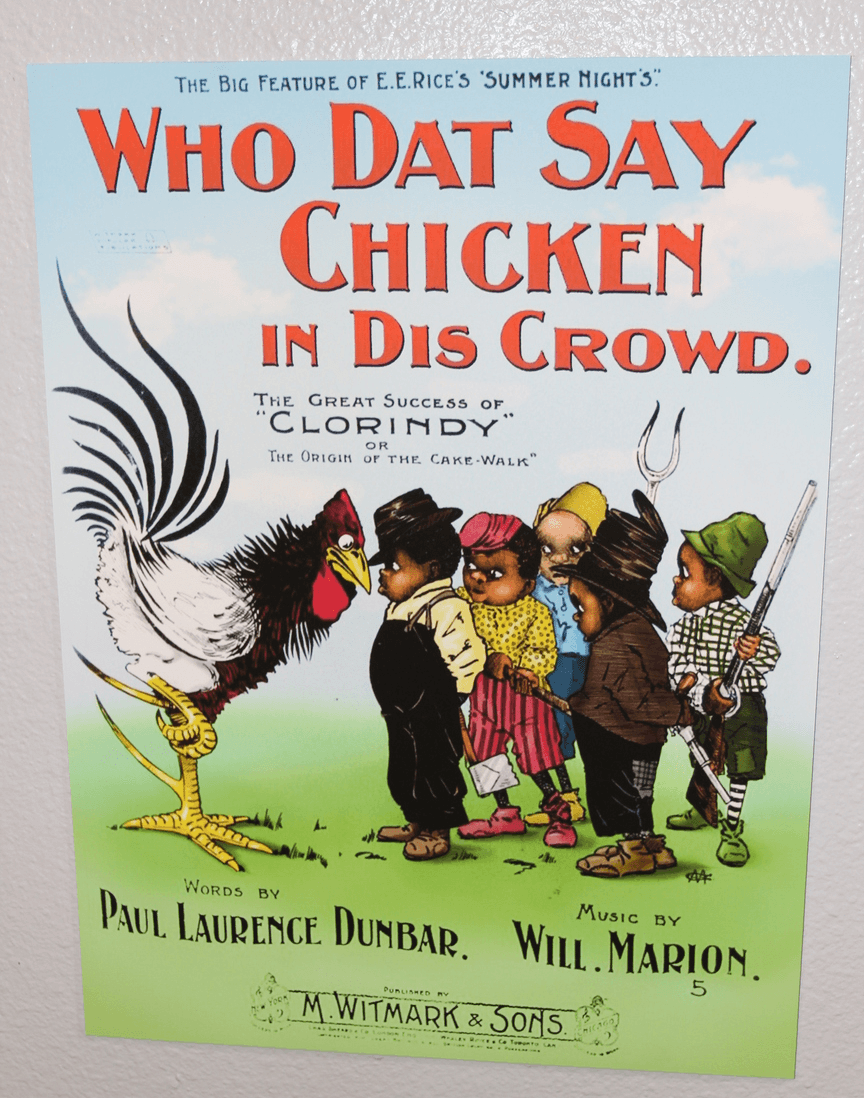

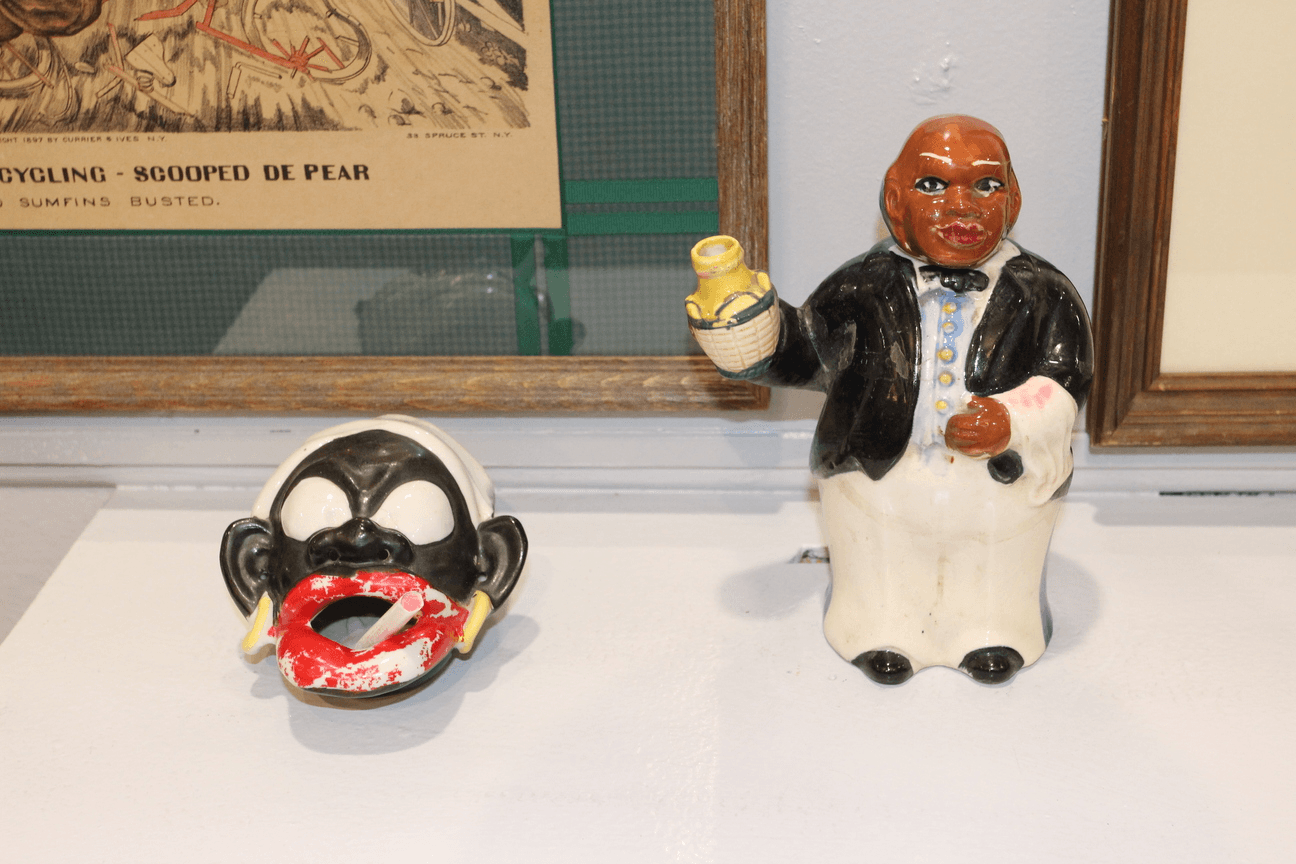

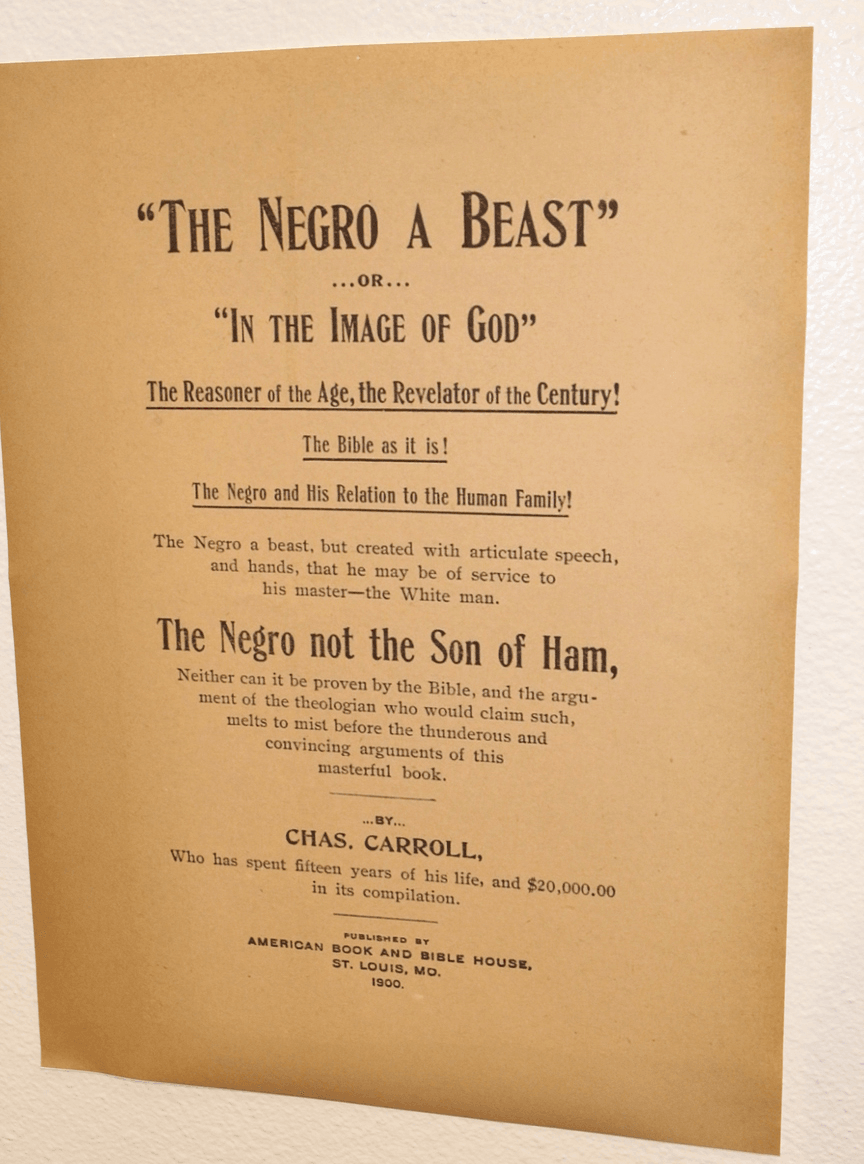

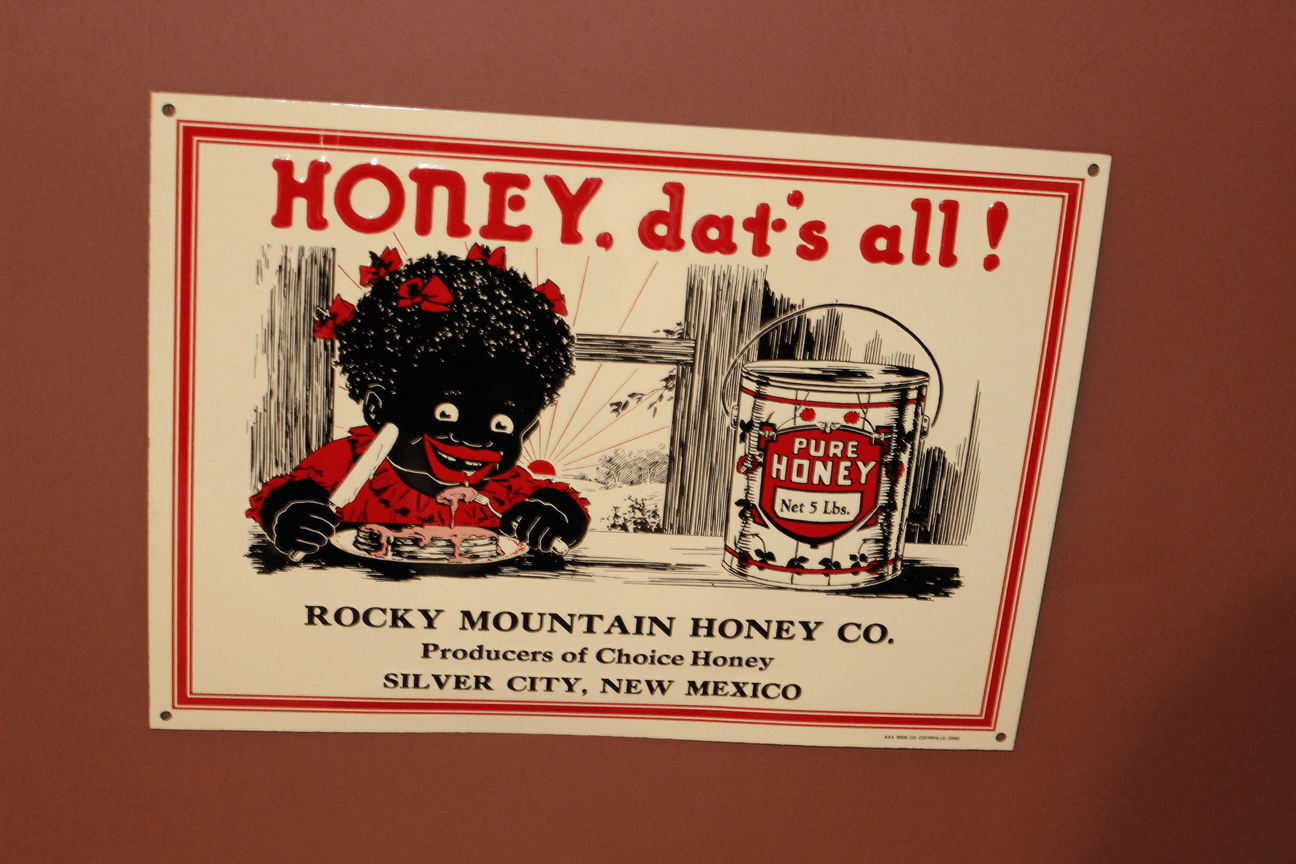

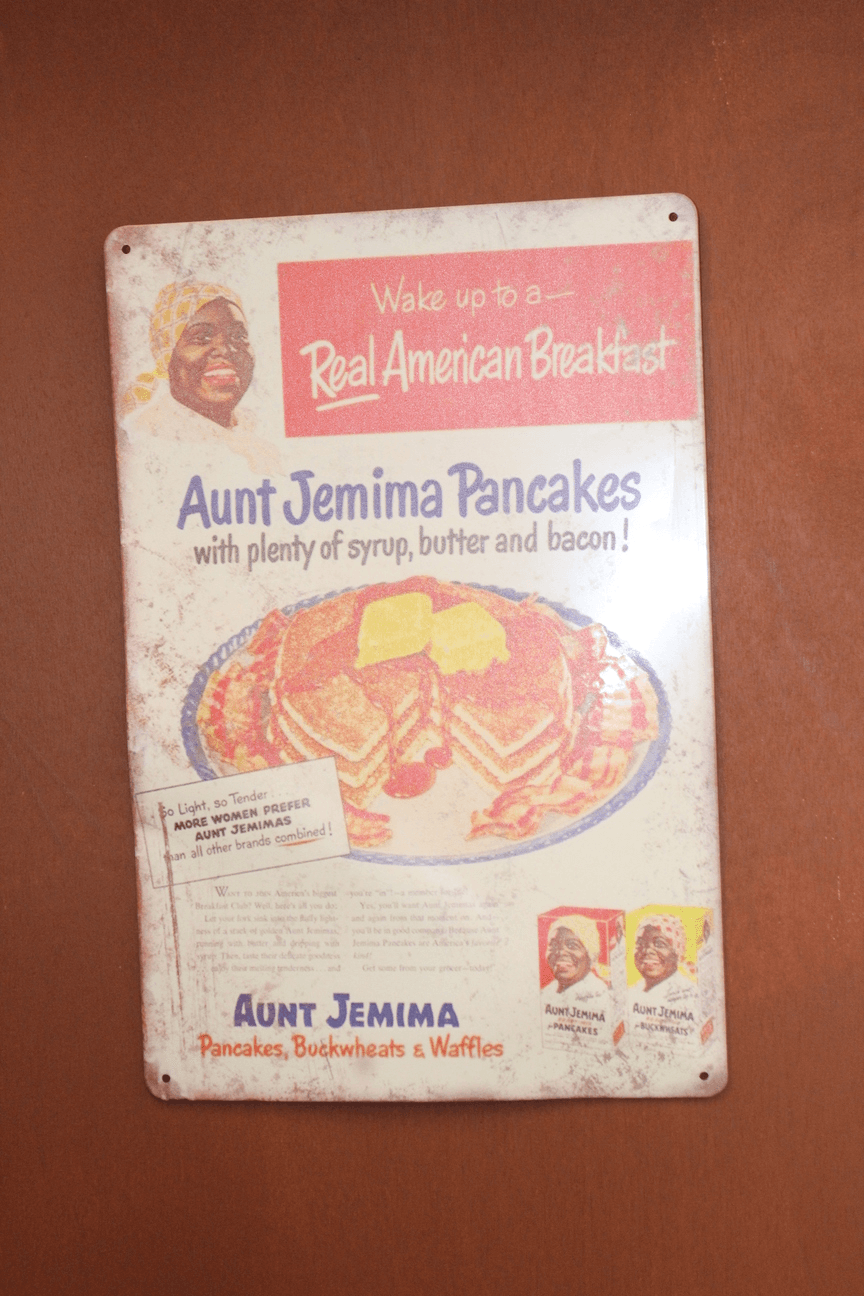

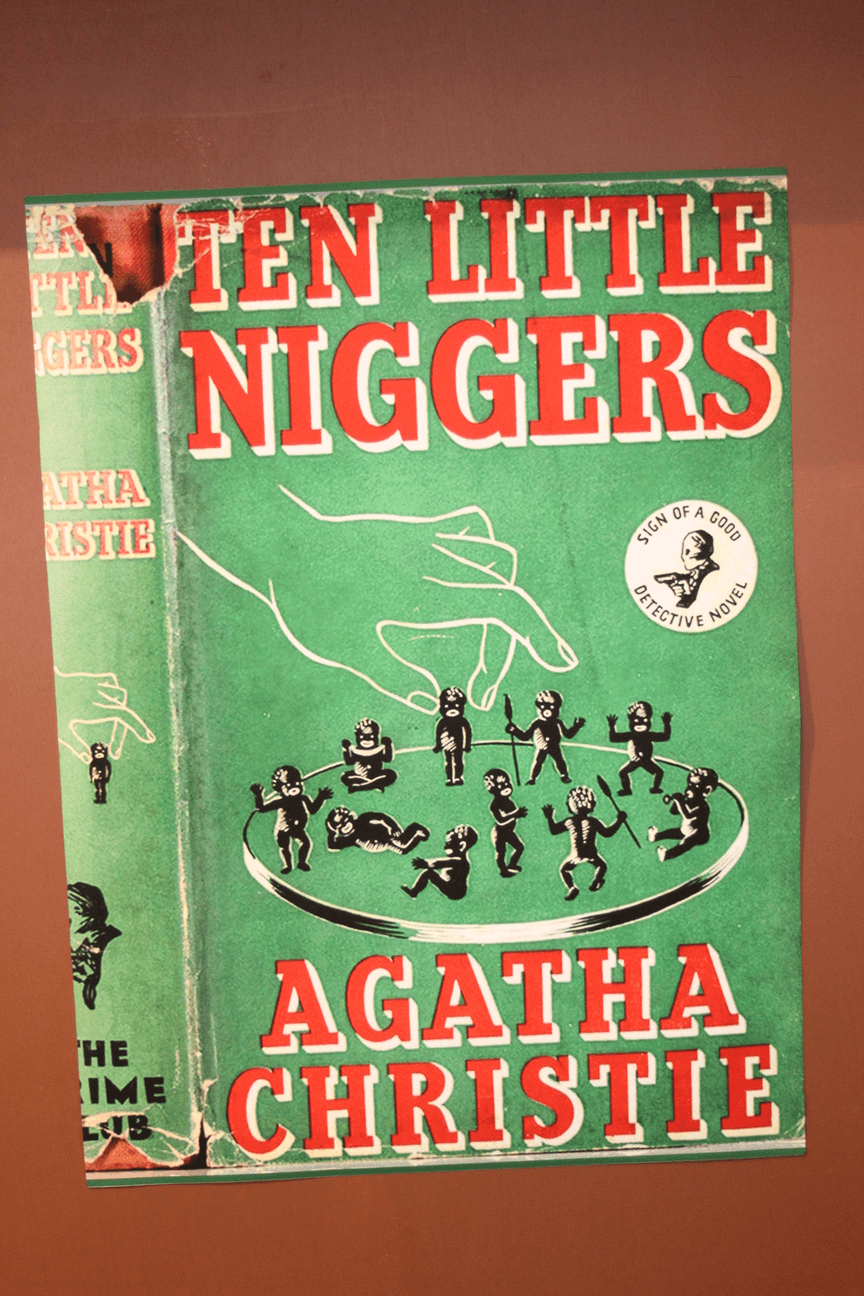

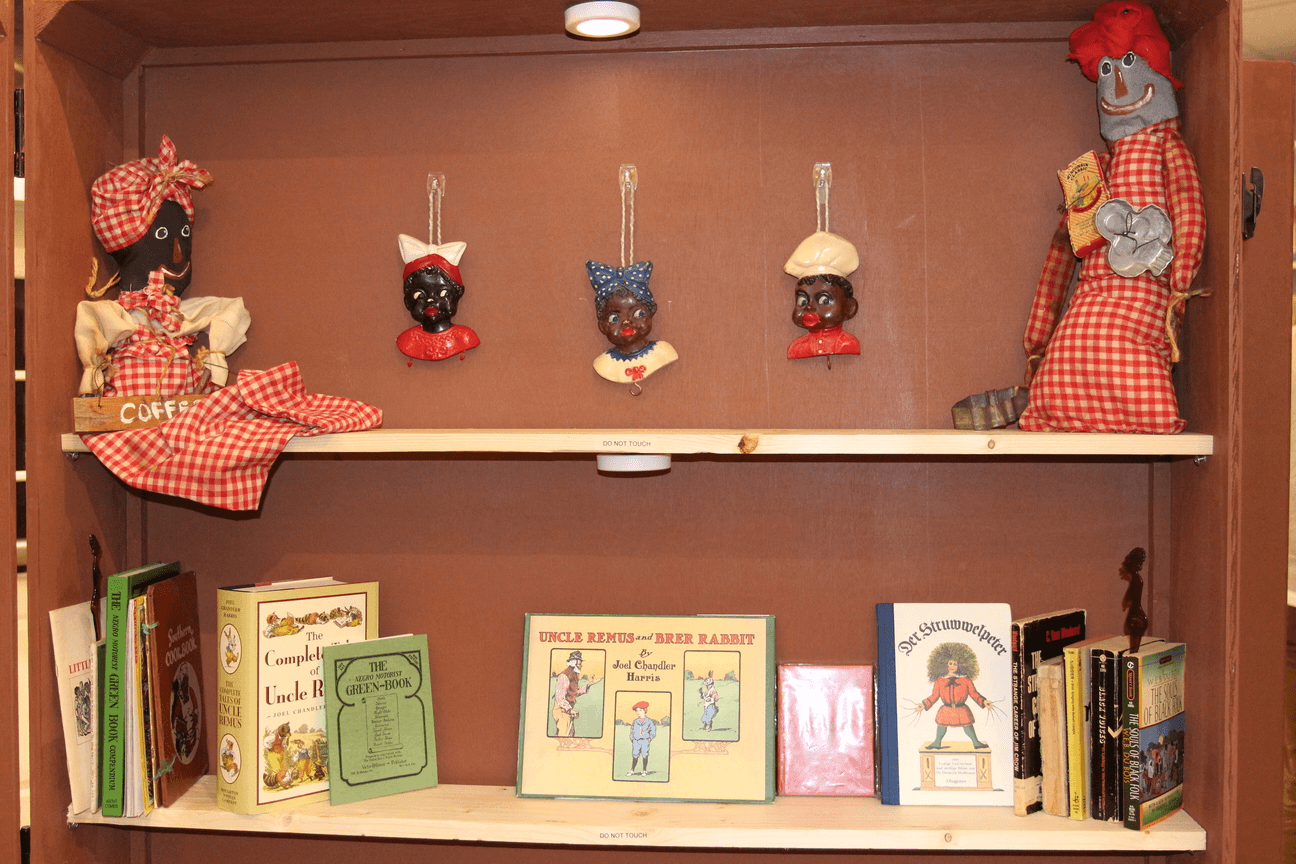

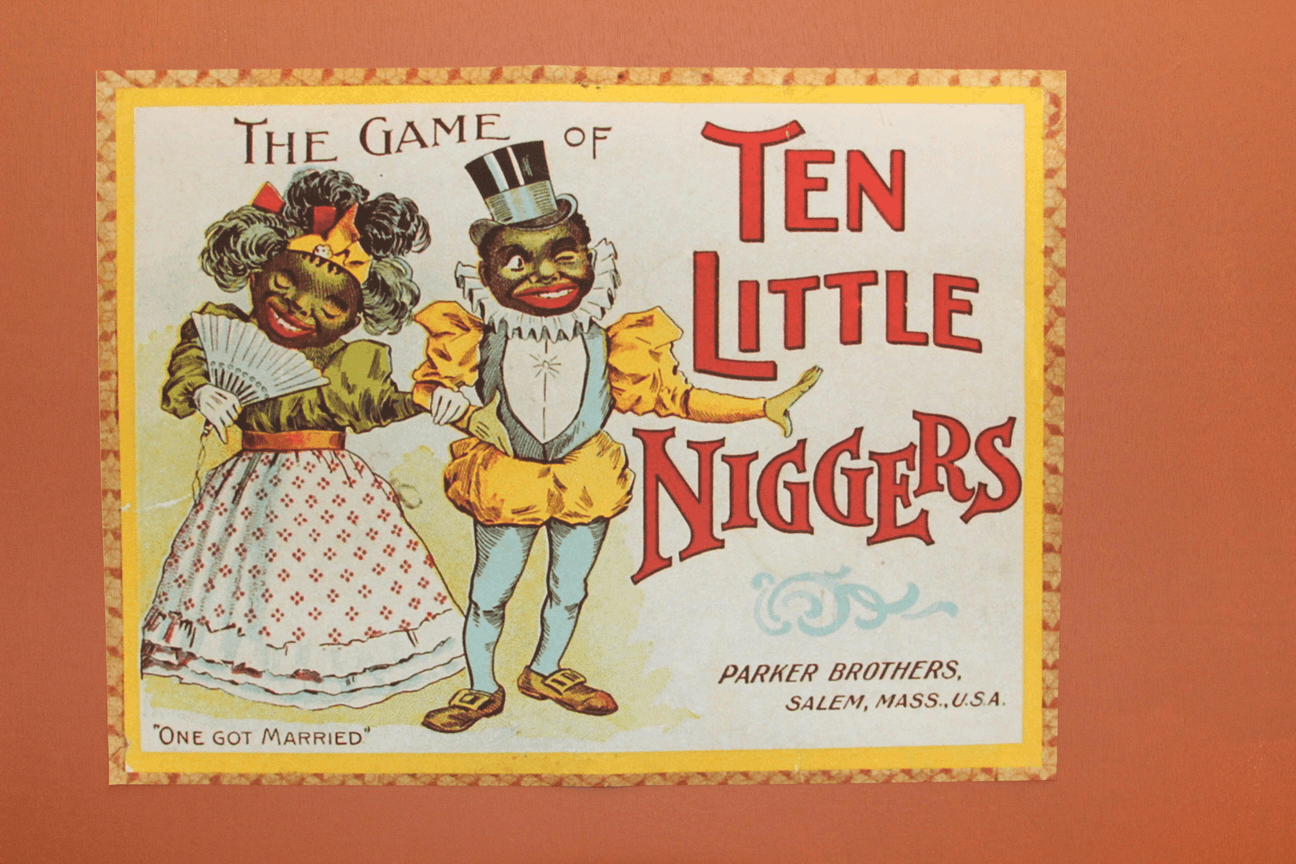

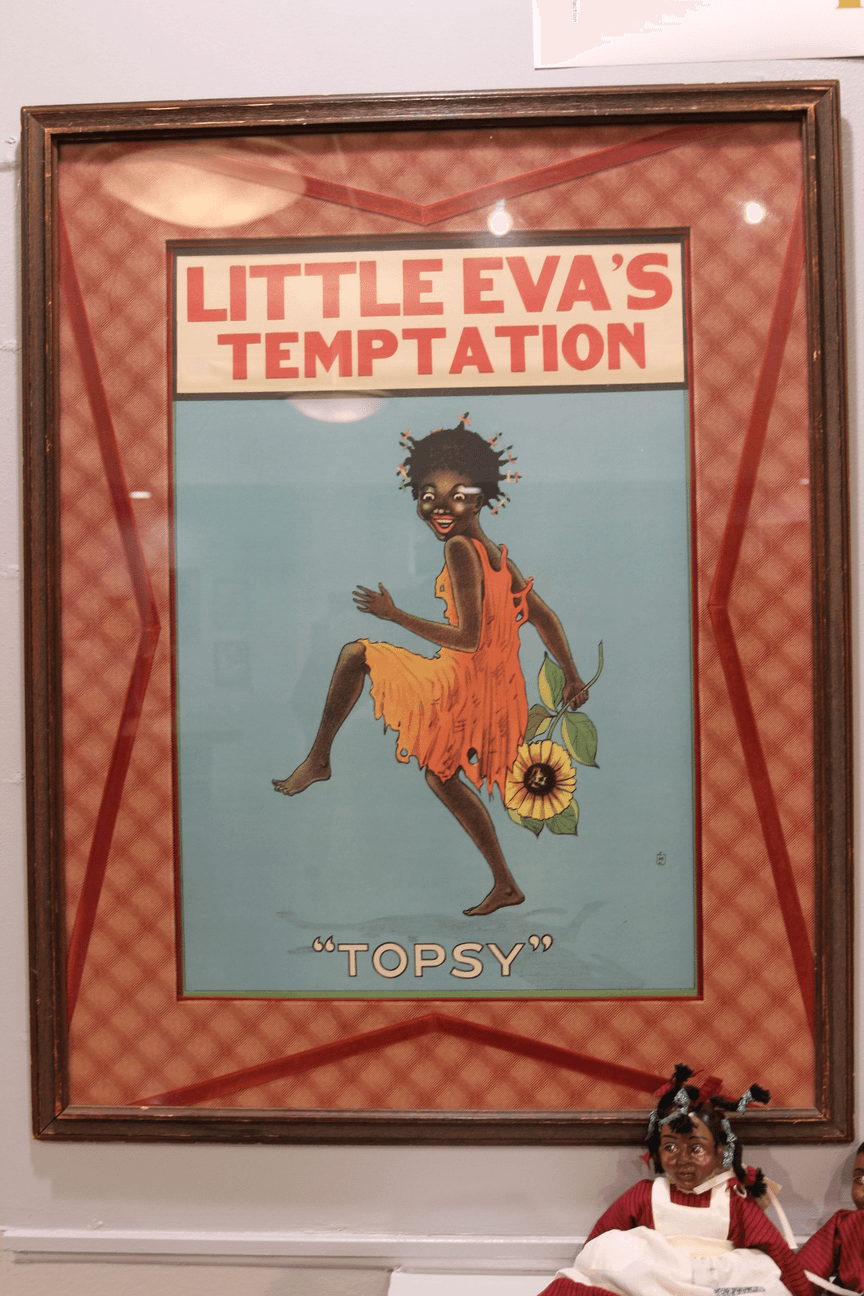

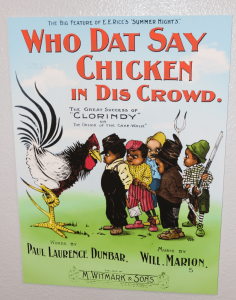

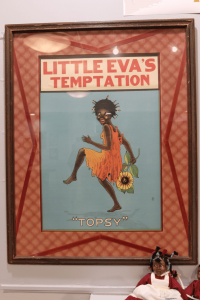

Clark explained there is a distinction between Black Americana and Jim Crow art. As Jim Crow memorabilia thrived between the 1880s and the 1960s, it was created by whites and depicted exaggerated stereotypes of African Americans, such as the female “mammy,” a male “brute caricature” or the grinning young “pickaninny.”

Visit the Woodson and take a step back in time to the Jim Crow era, where you’ll explore the stark realities of discrimination.

“They are not designed by African-American people, and they are not really about our lives,” he said. “They are what the whites thought would be oppressive to African Americans.”

Black Americana includes art created by Black people or artists counseled by Black people. Clark said some believe even today that racism isn’t an issue, yet “when you look at something that has occurred in the making of thousands of these pieces … you can see the insidious work that such a thing can cause, especially in large numbers and especially in homes daily.”

Clark found most of his pieces in thrift stores and yard sales, while some of the more valuable ones came from antique shops. He pointed out that the pieces attracted his attention because while the message they send about a people is evil, they are genius in their effectiveness of what they have caused.

Before acquiring a piece, he asks himself: “What is it telling me beyond its horribleness? What is it telling me beyond its intent? What are the unintended consequences of looking in their faces?”

Clark has displayed his collection in Florida and Georgia, and it has been chiefly in front of a white audience, Clark admitted.

During the Jim Crow period, African Americans were confronted by institutional discrimination and acts of individual discrimination and generally treated as second-class citizens.

As an educator, he displayed some of these pieces in his office and discovered that his Black students didn’t experience as much discomfort with them as did white students and white faculty members.

“The Black students were able to understand a collection like this once explained,” he said.

In his experience, Clark said that white people often become nervous when the subject of racism is brought up. He said they don’t realize they’re in the fight, but they are.

“You have to be involved in the solutions of what racism is about,” Clark asserted.

He revealed that white people have given him some of these pieces, in essence, trying to unburden themselves of them.

“They had them and are afraid of them, so they believe me to be a safe place to give them. I can understand why they’re nervous, but they also believe they’re history,” Clark explained.

There have been Black people upset by his collection. Clark knows some who have acquired such items to destroy them. White people, on the other hand, don’t want to even think about their existence at all — both viewpoints are too extreme for learning purposes, he averred.

“If you don’t really look at how this could happen, you will not understand how we got here,” Clark said. “And you certainly won’t know the proper, effective ways of solving the future.”

We must acknowledge the past and must do better to understand the difference between saying or doing a racist thing and comprehending the system of racism, he affirmed,

“You can get over someone calling you the n-word,” Clark said, “but when you are caught in a system, and you really don’t know how to break that system, that’s a problem. All of us are in it.”

Touching upon the specific items, he referred to the well-known image of Aunt Jemima as the “queen” of them all. He said she feeds people, and children will not go hungry when you see her around. Figures such as this are in our lives, Clark noted, adding that he knew some white women who were “Jemimas,” who did not feed him with food but with advice and direction in life.

“Look out for the Aunt Jemimas in your own life and what they do,” he said. How were you fed? Real good food or not so good? Some of us have had to shake loose of some of what you were fed.”

Aunt Jemima with her husband, Uncle Mose.

Indicating a depiction of Uncle Mose, whose name was changed from Uncle Rastus to avoid confusion with the Cream of Wheat character; he was the husband of Aunt Jemima. Clark noted that he appeared smiling with his hat in his hand, as though he wouldn’t harm a flea, but he is really absorbing information to relay.

“He’s right there listening, paying attention,” he explained. “Not loud. Some of us have had to learn to be Uncle Mose on the inside and how to take back the information. Who is that in your life, Black or white or other ones that can quietly speak the truth to you without the bravado, without the noise, but be just as effective?”

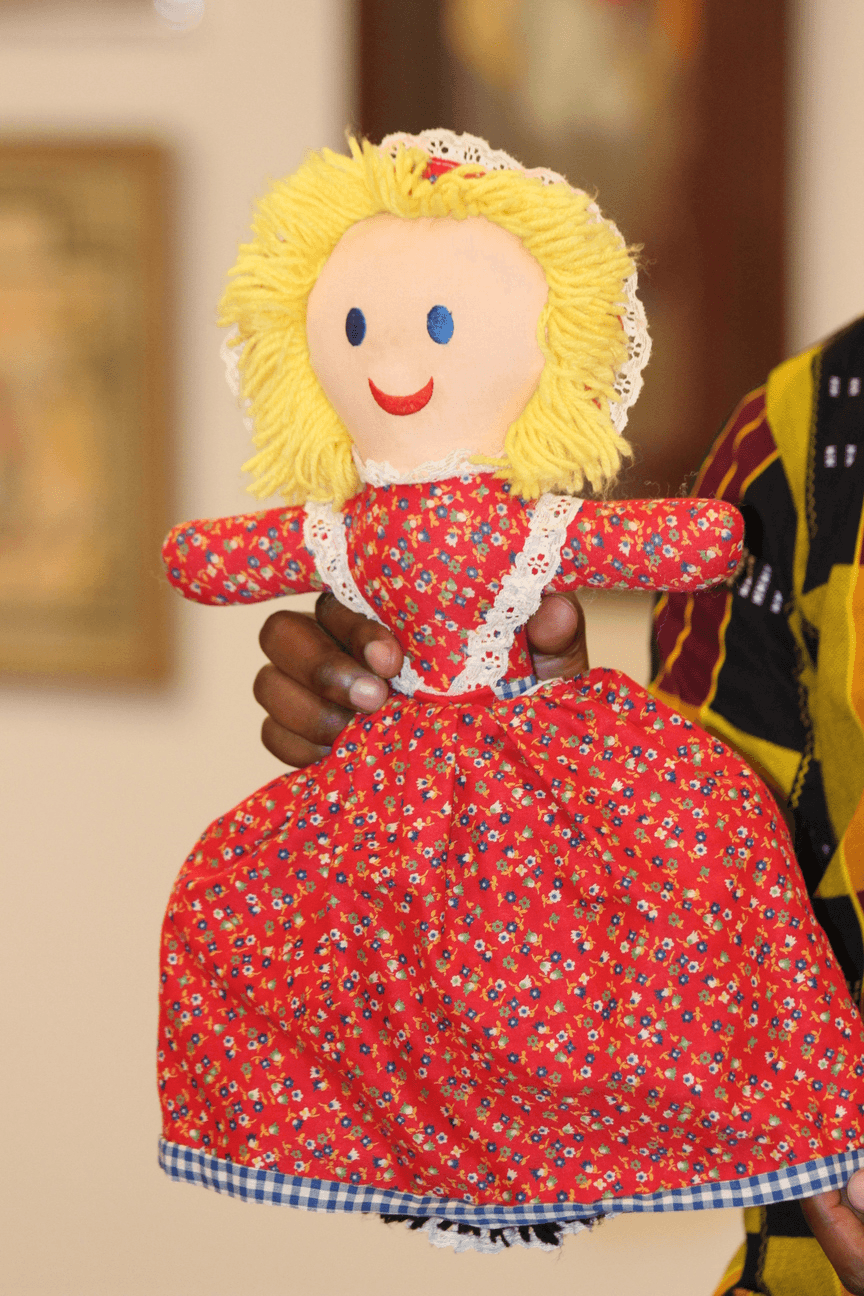

The oldest piece, the “topsy-turvy doll,” likely made by the enslaved for whites before the Civil War, could switch its appearance from a Black girl to a white girl when turned inside out.

Dr. Cody Clark likened the topsy-turvy doll to today’s code-switching.

“There’s not a Black person in this room that doesn’t know what code-switching is about. There are times when, because you are not being met with your true self, you will have to turn into that,” he said, pointing to the doll. “Your language must change; your actions must change because the larger community — the white community — won’t understand you. You can’t get that job if you don’t know how to switch and bring it back when you come home.”

Another doll in his collection from the 1960s was of a Black girl but with “white” characteristics, notably in the style of the hair and shape of the face and nose.

Over the years, African Americans became more educated, but it had unintended consequences, he noted.

“The more educated African Americans become, the more we shoulder the work in trying to make whites comfortable with us so that we are more digestible,” Clark said.

He encouraged whites to be more active in understanding what life is like for African Americans on a daily basis, even suggesting they attend a Black church to “be the uncomfortable one surrounded around Black people and see how you feel about it and learn what that’s like.”

On Tuesdays and Thursdays after 1 p.m. through the end of the month, you can gain insight on the collection from Dr. Clark himself at the Woodson, and on Feb. 29 at 6 p.m., don’t miss the closing reception of “Resilience & Revolution,” featuring Dr. Clark, as well as Clinton Byrd and Cedric Jones of the Montague Collection.

The Woodson African American Museum of Florida is located at 2240 9th Ave. S, St. Petersburg.

Photo Gallery

Post Views:

66