How to write dissertation

How To Write A Dissertation

Published

2 years agoon

By

chelsey1666How To Write A Dissertation

To The Candidate:

So, you are preparing to write a Ph.D. dissertation in an experimental area of Computer Science. Unless you have written many formal documents before, you are in for a surprise: it's difficult!

There are two possible paths to success:

-

- Planning Ahead.

Few take this path. The few who do leave the University so quickly that they are hardly noticed. If you want to make a lasting impression and have a long career as a graduate student, do not choose it.

- Perseverance.

All you really have to do is outlast your doctoral committee. The good news is that they are much older than you, so you can guess who will eventually expire first. The bad news is that they are more practiced at this game (after all, they persevered in the face of their doctoral committee, didn't they?).

- Planning Ahead.

Here are a few guidelines that may help you when you finally get serious about writing. The list goes on forever; you probably won't want to read it all at once. But, please read it before you write anything.

The General Idea:

- A thesis is a hypothesis or conjecture.

- A PhD dissertation is a lengthy, formal document that argues in defense of a particular thesis. (So many people use the term “thesis'' to refer to the document that a current dictionary now includes it as the third meaning of “thesis'').

- Two important adjectives used to describe a dissertation are “original'' and “substantial.'' The research performed to support a thesis must be both, and the dissertation must show it to be so. In particular, a dissertation highlights original contributions.

- The scientific method means starting with a hypothesis and then collecting evidence to support or deny it. Before one can write a dissertation defending a particular thesis, one must collect evidence that supports it. Thus, the most difficult aspect of writing a dissertation consists of organizing the evidence and associated discussions into a coherent form.

- The essence of a dissertation is critical thinking, not experimental data. Analysis and concepts form the heart of the work.

- A dissertation concentrates on principles: it states the lessons learned, and not merely the facts behind them.

- In general, every statement in a dissertation must be supported either by a reference to published scientific literature or by original work. Moreover, a dissertation does not repeat the details of critical thinking and analysis found in published sources; it uses the results as fact and refers the reader to the source for further details.

- Each sentence in a dissertation must be complete and correct in a grammatical sense. Moreover, a dissertation must satisfy the stringent rules of formal grammar (e.g., no contractions, no colloquialisms, no slurs, no undefined technical jargon, no hidden jokes, and no slang, even when such terms or phrases are in common use in the spoken language). Indeed, the writing in a dissertation must be crystal clear. Shades of meaning matter; the terminology and prose must make fine distinctions. The words must convey exactly the meaning intended, nothing more and nothing less.

- Each statement in a dissertation must be correct and defensible in a logical and scientific sense. Moreover, the discussions in a dissertation must satisfy the most stringent rules of logic applied to mathematics and science.

more about How to write dissertation linkedin.com .

What One Should Learn From The Exercise:

- All scientists need to communicate discoveries; the PhD dissertation provides training for for your dissertation communication with other scientists.

- Writing a dissertation requires a student to think deeply, to organize technical discussion, to muster arguments that will convince other scientists, and to follow rules for rigorous, formal presentation of the arguments and discussion.

A Rule Of Thumb:

Good writing is essential in a dissertation. However, good writing cannot compensate for a paucity of ideas or concepts. Quite the contrary, a clear presentation always exposes weaknesses.

Definitions And Terminology:

- Each technical term used in a dissertation must be defined either by a reference to a previously published definition (for standard terms with their usual meaning) or by a precise, unambiguous definition that appears before the term is used (for a new term or a standard term used in an unusual way).

- Each term should be used in one and only one way throughout the dissertation.

- The easiest way to avoid a long series of definitions is to include a statement: “the terminology used throughout this document follows that given in [CITATION].'' Then, only define exceptions.

- The introductory chapter can give the intuition (i.e., informal definitions) of terms provided they are defined more precisely later.

Terms And Phrases To Avoid:

- adverbs

- Mostly, they are very often overly used. Use strong words instead. For example, one could say, “Writers abuse adverbs.''

- jokes or puns

- They have no place in a formal document.

- “bad'', “good'', “nice'', “terrible'', “stupid''

- A scientific dissertation does not make moral judgements. Use “incorrect/correct'' to refer to factual correctness or errors. Use precise words or phrases to assess quality (e.g., “method A requires less computation than method B''). In general, one should avoid all qualitative judgements.

- “true'', “pure'',

- In the sense of “good'' (it is judgemental).

- “perfect''

- Nothing is.

- “an ideal solution''

- You're judging again.

- “today'', “modern times''

- Today is tomorrow's yesterday.

- “soon''

- How soon? Later tonight? Next decade?

- “we were surprised to learn…''

- Even if you were, so what?

- “seems'', “seemingly'',

- It doesn't matter how something appears;

- “would seem to show''

- all that matters are the facts.

- “in terms of''

- usually vague

- “based on'', for your dissertation “X-based'', “as the basis of''

- careful; can be vague

- “different''

- Does not mean “various''; different than what?

- “in light of''

- colloquial

- “lots of''

- vague & colloquial

- “kind of''

- vague & colloquial

- “type of''

- vague & colloquial

- “something like''

- vague & colloquial

- “just about''

- vague & colloquial

- “number of''

- vague; do you mean “some'', “many'', or “most''? A quantitative statement is preferable.

- “due to''

- colloquial

- “probably''

- only if you know the statistical probability (if you do, state it quantitatively

- “obviously, clearly''

- be careful: obvious/clear to everyone?

- “simple''

- Can have a negative connotation, as in “simpleton''

- “along with''

- Just use “with''

- “actually, really''

- define terms precisely to eliminate the need to clarify

- “the fact that''

- makes it a meta-sentence; rephrase

- “this'', “that''

- As in “This causes concern.'' Reason: “this'' can refer to the subject of the previous sentence, the entire previous sentence, the entire previous paragraph, the entire previous section, etc. More important, it can be interpreted in the concrete sense or in the meta-sense. For example, in: “X does Y. This means …'' the reader can assume “this'' refers to Y or to the fact that X does it. Even when restricted (e.g., “this computation…''), the phrase is weak and often ambiguous.

- “You will read about…''

- The second person has no place in a formal dissertation.

- “I will describe…''

- The first person has no place in a formal dissertation. If self-reference is essential, phrase it as “Section 10 describes…''

- “we'' as in “we see that''

- A trap to avoid. Reason: almost any sentence can be written to begin with “we'' because “we'' can refer to: the reader and author, the author and advisor, the author and research team, experimental computer scientists, the entire computer science community, the science community, or some other unspecified group.

- “Hopefully, the program…''

- Computer programs don't hope, not unless they implement AI systems. By the way, if you are writing an AI thesis, talk to someone else: AI people have their own system of rules.

- “…a famous researcher…''

- It doesn't matter who said it or who did it. In fact, such statements prejudice the reader.

- Be Careful When Using “few, most, all, any, every''.

- A dissertation is precise. If a sentence says “Most computer systems contain X'', you must be able to defend it. Are you sure you really know the facts? How many computers were built and sold yesterday?

- “must'', “always''

- Absolutely?

- “should''

- Who says so?

- “proof'', “prove''

- Would a mathematician agree that it's a proof?

- “show''

- Used in the sense of “prove''. To “show'' something, you need to provide a formal proof.

- “can/may''

- Your mother probably told you the difference.

Voice:

- Use active constructions. For example, say “the operating system starts the device'' instead of “the device is started by the operating system.''

Tense:

- Write in the present tense. For example, say “The system writes a page to the disk and then uses the frame…'' instead of “The system will use the frame after it wrote the page to disk…''

Define Negation Early:

- Example: say “no data block waits on the output queue'' instead of “a data block awaiting output is not on the queue.''

Grammar And Logic:

- Be careful that the subject of each sentence really does what the verb says it does. Saying “Programs must make procedure calls using the X instruction'' is not the same as saying “Programs must use the X instruction when they call a procedure.'' In fact, the first is patently false! Another example: “RPC requires programs to transmit large packets'' is not the same as “RPC requires a mechanism that allows programs to transmit large packets.''

All computer scientists should know the rules of logic. Unfortunately the rules are more difficult to follow when the language of discourse is English instead of mathematical symbols. For example, the sentence “There is a compiler that translates the N languages by…'' means a single compiler exists that handles all the languages, while the sentence “For each of the N languages, there is a compiler that translates…'' means that there may be 1 compiler, 2 compilers, or N compilers. When written using mathematical symbols, the difference are obvious because “for all'' and “there exists'' are reversed.

Focus On Results And Not The People/Circumstances In Which They Were Obtained:

- “After working eight hours in the lab that night, we realized…'' has no place in the dissertation. It doesn't matter when you realized it or how long you worked to obtain the answer. Another example: “Jim and I arrived at the numbers shown in Table 3 by measuring…'' Put an acknowledgement to Jim in the dissertation, but do not include names (even your own) in the main body. You may be tempted to document a long series of experiments that produced nothing or a coincidence that resulted in success. Avoid it completely. In particular, do not document seemingly mystical influences (e.g., “if that cat had not crawled through the hole in the floor, we might not have discovered the power supply error indicator on the network bridge''). Never attribute such events to mystical causes or imply that strange forces may have affected your results. Summary: stick to the plain facts. Describe the results without dwelling on your reactions or events that helped you achieve them.

Avoid Self-Assessment (both praise and criticism):

- Both of the following examples are incorrect: “The method outlined in Section 2 represents a major breakthrough in the design of distributed systems because…'' “Although the technique in the next section is not earthshaking,…''

References To Extant Work:

- One always cites papers, not authors. Thus, one uses a singular verb to refer to a paper even though it has multiple authors. For example “Johnson and Smith [J&S90] reports that…''

Avoid the phrase “the authors claim that X''. The use of “claim'' casts doubt on “X'' because it references the authors' thoughts instead of the facts. If you agree “X'' is correct, simply state “X'' followed by a reference. If one absolutely must reference a paper instead of a result, say “the paper states that…'' or “Johnson and Smith [J&S 90] presents evidence that…''.

Concept Vs. Instance:

- A reader can become confused when a concept and an instance of it are blurred. Common examples include: an algorithm and a particular program that implements it, a programming language and a compiler, a general abstraction and its particular implementation in a computer system, a data structure and a particular instance of it in memory.

Terminology For Concepts And Abstractions

- When defining the terminology for a concept, be careful to decide precisely how the idea translates to an implementation. Consider the following discussion:

VM systems include a concept known as an address space. The system dynamically creates an address space when a program needs one, and destroys an address space when the program that created the space has finished using it. A VM system uses a small, finite number to identify each address space. Conceptually, one understands that each new address space should have a new identifier. However, if a VM system executes so long that it exhausts all possible address space identifiers, it must reuse a number.

The important point is that the discussion only makes sense because it defines “address space'' independently from “address space identifier''. If one expects to discuss the differences between a concept and its implementation, the definitions must allow such a distinction.

Knowledge Vs. Data

- The facts that result from an experiment are called “data''. The term “knowledge'' implies that the facts have been analyzed, condensed, or combined with facts from other experiments to produce useful information.

Cause and Effect:

- A dissertation must carefully separate cause-effect relationships from simple statistical correlations. For example, even if all computer programs written in Professor X's lab require more memory than the computer programs written in Professor Y's lab, it may not have anything to do with the professors or the lab or the programmers (e.g., maybe the people working in professor X's lab are working on applications that require more memory than the applications in professor Y's lab).

Drawing Only Warranted Conclusions:

- One must be careful to only draw conclusions that the evidence supports. For example, if programs run much slower on computer A than on computer B, one cannot conclude that the processor in A is slower than the processor in B unless one has ruled out all differences in the computers' operating systems, input or output devices, memory size, memory cache, or internal bus bandwidth. In fact, one must still refrain from judgement unless one has the results from a controlled experiment (e.g., running a set of several programs many times, each when the computer is otherwise idle). Even if the cause of some phenomenon seems obvious, one cannot draw a conclusion without solid, for your dissertation supporting evidence.

Commerce and Science:

- In a scientific dissertation, one never draws conclusions about the economic viability or commercial success of an idea/method, nor does one speculate about the history of development or origins of an idea. A scientist must remain objective about the merits of an idea independent of its commercial popularity. In particular, a scientist never assumes that commercial success is a valid measure of merit (many popular products are neither well-designed nor well-engineered). Thus, statements such as “over four hundred vendors make products using technique Y'' are irrelevant in a dissertation.

Politics And Science:

- A scientist avoids all political influence when assessing ideas. Obviously, it should not matter whether government bodies, political parties, religious groups, or other organizations endorse an idea. More important and often overlooked, it does not matter whether an idea originated with a scientist who has already won a Nobel prize or a first-year graduate student. One must assess the idea independent of the source.

Canonical Organization:

- In general, every dissertation must define the problem that motivated the research, tell why that problem is important, tell what others have done, describe the new contribution, document the experiments that validate the contribution, and draw conclusions. There is no canonical organization for a dissertation; each is unique. However, novices writing a dissertation in the experimental areas of CS may find the following example a good starting point:

-

Chapter 1: Introduction

- An overview of the problem; why it is important; a summary of extant work and a statement of your hypothesis or specific question to be explored. Make it readable by anyone.

-

Chapter 2: Definitions

- New terms only. Make the definitions precise, concise, and unambiguous.

-

Chapter 3: Conceptual Model

- Describe the central concept underlying your work. Make it a “theme'' that ties together all your arguments. It should provide an answer to the question posed in the introduction at a conceptual level. If necessary, add another chapter to give additional reasoning about the problem or its solution.

-

Chapter 4: Experimental Measurements

- Describe the results of experiments that provide evidence in support of your thesis. Usually experiments either emphasize proof-of-concept (demonstrating the viability of a method/technique) or efficiency (demonstrating that a method/technique provides better performance than those that exist).

-

Chapter 5: Corollaries And Consequences

- Describe variations, extensions, or other applications of the central idea.

-

Chapter 6: Conclusions

- Summarize what was learned and how it can be applied. Mention the possibilities for future research.

-

Abstract:

- A short (few paragraphs) summary of the dissertation. Describe the problem and the research approach. Emphasize the original contributions.

-

Suggested Order For Writing:

- The easiest way to build a dissertation is inside-out. Begin by writing the chapters that describe your research (3, 4, and 5 in the above outline). Collect terms as they arise and keep a definition for each. Define each technical term, even if you use it in a conventional manner.

Organize the definitions into a separate chapter. Make the definitions precise and formal. Review later chapters to verify that each use of a technical term adheres to its definition. After reading the middle chapters to verify terminology, write the conclusions. Write the introduction next. Finally, complete an abstract.

Key To Success:

- By the way, there is a key to success: practice. No one ever learned to write by reading essays like this. Instead, you need to practice, practice, practice. Every day.

Parting thoughts:

- We leave you with the following ideas to mull over. If they don't mean anything to you now, revisit them after you finish writing a dissertation.

How to write dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Your Ultimate Guide

Published

2 years agoon

November 17, 2023By

hyzbianca17How to Write a Dissertation: Your Ultimate Guide

Consider this intriguing tidbit – renowned physicist Albert Einstein's groundbreaking theory of relativity, which revolutionized our understanding of the universe, was initially proposed as part of his doctoral dissertation. This singular fact underscores that even the most profound and transformative ideas, such as those underpinning the theory of relativity, can emerge from the crucible of writing a dissertation. Your own research, when pursued with diligence and insight, could hold the key to unlocking the next big discovery in your field, just as Einstein's did.

How to Write a Dissertation: Short Description

In this comprehensive guide, our experts will delve deep into the intricate world of dissertations, uncovering what exactly a dissertation is, its required length, and its key characteristics. With expert insights and practical advice, you'll discover how to write a dissertation step by step that not only meets rigorous academic standards but also showcases your unique contributions to your field of study. From selecting a compelling research topic to conducting thorough literature reviews, from structuring your chapters to mastering the art of academic writing, this dissertation assistance service guide covers every aspect of dissertation.

What Is a Dissertation: Understanding the Academic Endeavour

At its core, a dissertation represents the pinnacle of your academic journey—an intellectual endeavor that encapsulates your years of learning, research, and critical thinking. But what exactly is a dissertation beyond the weighty definition it carries? Let our expert essay writer peel back the layers for you to understand this academic masterpiece.

A Quest for Mastery: A dissertation is not just a lengthy paper; it's a quest for mastery in a specific subject or field. It's your opportunity to dive deeper into a topic that has captured your intellectual curiosity to the point where you become an authority, a trailblazer in that area.

Original Contribution: Unlike term papers or essays, dissertation examples are expected to make an original contribution to your field of study. It's not about rehashing existing knowledge but rather about advancing it. It's your chance to bring something new, something insightful, and something that can potentially reshape the way others think about your area of expertise.

A Conversation Starter: Think of a dissertation as a conversation starter within academia. It's your voice in the ongoing dialogue of your field. When you embark on this journey, you're joining a centuries-old conversation, contributing your insights and perspectives to enrich the collective understanding.

learn more about How to write dissertation https://centrofreire.com/blog/index.php?entryid=64968 .

Rigorous Inquiry: Dissertation writing is a rigorous process that demands thorough research, critical analysis, and well-supported arguments. It's a demonstration of your ability to navigate the sea of existing literature, identify gaps in knowledge, and construct a solid intellectual bridge to fill those gaps.

A Personal Journey: Lastly, a dissertation is a personal journey. It's your opportunity to demonstrate not only your academic prowess but also your growth as a scholar. It's a testament to your determination, discipline, and passion for knowledge.

How to Start a Dissertation: Essential First Steps

Imagine starting a big adventure, like climbing a tall mountain. That's what learning how to write a dissertation is like. You might feel a mix of excitement and nervousness but don't worry. These first steps will help you get going on the right path.

1. Brainstorm Your Ideas

Think of this step as brainstorming, like when you come up with lots of ideas. Write down topics or questions that you find interesting. It's like gathering the pieces of a puzzle.

2. Choose Your Topic

Next, pick one of those topics for dissertation that you're really passionate about. It should also be something related to your studies. This is like picking the best puzzle piece to start with.

3. Read and Learn

Now, start reading books and articles about your chosen topic. This is like finding clues on a treasure map. Other smart people have studied this topic, and you can learn from them.

4. Decide How to Study

Think about how you'll gather information for your dissertation. Will you use numbers and data like a scientist? Or will you talk to people and observe things, like a detective? This is important to plan early.

5. Show Your Plan

Before you start writing, share your plan with your teachers or advisors. It's like showing them a preview of your work. They can give you advice and make sure you're on the right track.

6. Start Writing

Now, it's time to put your thoughts into words. Write your dissertation like you're telling a story. Make sure it all makes sense and flows nicely, much like when you're mastering how to write an argumentative essay.

7. Get Feedback

Show your work to others, like your friends or teachers. They can give you feedback, which is like helpful suggestions. Use their advice to make your work even better; this will also ease your dissertation defense. You can also seek advice to buy dissertation online.

How Long Is a Dissertation: Navigating the Length Requirements

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to the question of how long a dissertation should be. The length of your dissertation will depend on various factors, including university guidelines, academic discipline, research complexity, and the nature of your study. Let's navigate the length requirements with rough estimates for bachelor's, master's, and doctoral dissertations.

Now, let's uncover various factors that influence dissertation length:

University Guidelines and Departmental Requirements:

- University rules and department norms set your dissertation's length.

- Check for word/page limits and format rules early in your work.

Academic Discipline:

- Disciplines vary in dissertation length.

- Humanities/social sciences tend to be longer; science/tech are shorter.

Research Complexity and Depth:

- Complex research needs more pages.

- Simpler or narrower topics result in shorter dissertations.

Nature of the Study:

- Qualitative research with interviews and data analysis needs more pages.

- Quantitative studies can be more concise.

Dissertation Type:

- Some programs offer flexible formats.

- Alternative formats can lead to shorter dissertations.

Your Advisor's Guidance:

- Your advisor can offer lengthy advice.

- Benefit from their field expertise.

Is Your Dissertation Giving You Stress Instead of a Ph.D. Badge of Honor?

Why not let our experts be the pain relief you need? Get the genius you deserve with our dissertation help!

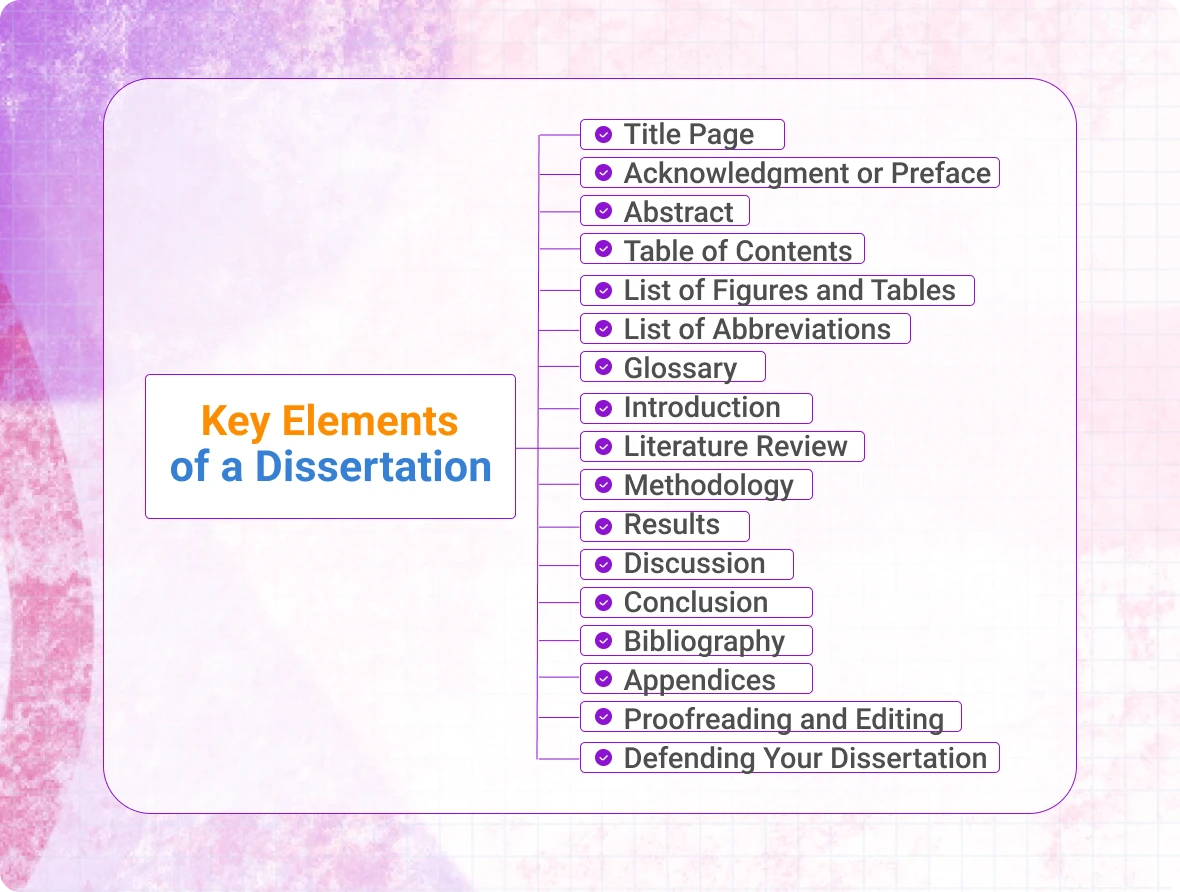

Dissertation Plan: Key Insights to Remember

In this section, we will explore the key insights essential for creating a dissertation plan that not only outlines your research but also paves the way for a successful academic endeavor. From defining your research objectives to establishing a robust methodology and timeline, let's delve into the crucial elements that will shape your dissertation into a scholarly masterpiece.

Title Page

The title page is the opening page of your dissertation and serves as the cover. It sets the stage for your dissertation and provides essential information for anyone reviewing your work. The dissertation title page typically contains the following information:

- Title of the Dissertation: This should be a concise, descriptive title that accurately reflects the content and scope of your research.

- Your Full Name: Your full name should be prominently displayed, usually centered on the page.

- Institutional Affiliation: The name of your academic institution, such as your university or college, is included.

- Degree Information: Indicate the type of degree (e.g., Bachelor's, Master's, Ph.D.) and the academic department or school.

- Date of Submission: This is the date when you are submitting your dissertation for evaluation.

- Your Advisor's Name: Include the name of your dissertation advisor or supervisor.

Acknowledgment or Preface

The acknowledgment or preface is a section of your dissertation where you have the opportunity to express gratitude and acknowledge the individuals, institutions, or organizations that have supported and contributed to your research. In this section, you can:

- Thank Your Advisors and Committee: Express your appreciation for the guidance, support, and expertise of your dissertation committee members and academic advisors.

- Acknowledge Funding Sources: If your research received financial support from grants, scholarships, or research fellowships, acknowledge these sources.

- Recognize Family and Friends: You can also mention the emotional and personal support you received from family and friends during your academic journey.

Abstract

A key element when understanding how to write a dissertation is the abstract. It is a concise summary of your entire dissertation and serves as a brief overview that allows readers to quickly understand the purpose, methodology, findings, and significance of your research. Key components of an abstract include:

- Research Problem/Objective: Clearly state the research problem or objective that your dissertation addresses.

- Methodology: Describe the methods and approaches you used to conduct your research.

- Key Findings: Summarize the most significant findings or results of your study.

- Conclusions: Highlight the implications of your research and any recommendations if applicable.

- Keywords: Include a list of relevant keywords that can help others find your dissertation in academic databases.

An abstract is typically limited to a certain word count (about 300 to 500 words), so it requires precise and concise writing to capture the essence of your dissertation effectively. It's often the first section that readers will see, so it should be compelling and informative.

Table of Contents

While writing a dissertation, you must include the table of contents, which is a roadmap of the sections and subsections within your dissertation. It serves as a navigation tool, allowing readers to quickly locate specific chapters, sections, and headings. It should include:

- Chapter Titles: List the main chapters or sections of your dissertation, along with their corresponding page numbers.

- Subheadings: Include subsections and subheadings within each chapter, along with their page numbers.

- Appendices and Supplementary Material: If your dissertation includes appendices or supplementary material, estesparkrentals.com include these in the Table of Contents as well.

List of Figures and Tables

If your dissertation includes visual elements such as graphs, charts, tables, or images, it's essential to provide a List of Figures and Tables. These lists help readers quickly locate specific visual content within your dissertation. Each list should include:

- Figure/Table Number: Assign a unique number to each figure or table used in your dissertation.

- Figure/Table Title: Provide a brief but descriptive title for each figure or table.

- Page Number: Indicate the page number where each figure or table is located.

The List of Figures and Tables is especially useful for readers who may want to reference or study the visual data presented in your dissertation without having to search through the entire document.

List of Abbreviations

In dissertation writing, it's helpful to include a list of abbreviations. This list provides definitions or explanations for any acronyms, royalnauticals.com initialisms, or abbreviations used in your dissertation. Elements of the list may include:

- Abbreviation: List each abbreviation or acronym in alphabetical order.

- Full Explanation: Provide the full phrase or term that the abbreviation represents.

- Page Number: Optionally, you can include the page number where each abbreviation is first introduced in the text.

Glossary

A glossary is an optional but valuable section in a dissertation, especially when your research involves technical terms, specialized terminology, or unique jargon. This section provides readers with definitions and explanations for key terms used throughout your dissertation. Elements of a glossary include:

- Term: List each term in alphabetical order.

- Definition: Provide a clear and concise explanation or definition of each term.

Introduction

The introduction is a critical section of your dissertation, as it sets the stage for your research and provides readers with an overview of what to expect. In the dissertation introduction:

- Introduce the Research Problem: Clearly state the research problem or question your dissertation aims to address. You can also explore different types of tone to use in your writing.

- Provide Context: Explain the broader context and significance of your research within your field of study.

- State the Purpose and Objectives: Outline the goals and objectives of your research.

- Hypotheses or Research Questions: Present any hypotheses or specific research questions that guide your investigation.

- Scope and Limitations: Define the scope of your research and any limitations or constraints.

- Outline of the Dissertation: Give a brief overview of the structure of your dissertation, including the main chapters.

Literature Review

The Literature Review is a comprehensive examination of existing scholarly work and research relevant to your dissertation topic. In this section:

- Review Existing Literature: Summarize and analyze primary and secondary sources, including theories and research findings related to your topic.

- Identify Gaps: Highlight any gaps or areas where further research is needed.

- Theoretical Framework: Discuss the theoretical framework that informs your research.

- Methodological Approach: Explain the research methods you'll use and why they are appropriate.

- Synthesize Information: Organize the literature logically and thematically to show how it informs your research.

Methodology

The Methodology section of your dissertation outlines the research methods, procedures, and approaches you employed to conduct your study. This section is crucial because it provides a clear explanation of how your preliminary research was carried out, allowing readers to assess the validity and reliability of your findings. Elements typically found in the Methodology section include:

- Research Design: Describe the overall structure and design of your study, such as whether it is experimental, observational, or qualitative.

- Data Collection: Explain the methods used to gather data, including surveys, interviews, experiments, observations, or document analysis.

- Sampling: Detail how you selected your sample or participants, including criteria and procedures.

- Data Analysis: Outline the analytical techniques used to process and interpret your data.

- Ethical Considerations: Address any ethical issues related to your research, such as informed consent and data privacy.

Results

In this section of dissertation writing, you present the outcomes of your research without interpretation or discussion. The results section is where you report your findings objectively and in a clear, organized manner. Key components of the Results section include:

- Data Presentation: Present your data using tables, charts, graphs, or textual descriptions, depending on the nature of the data.

- Statistical Analysis: If applicable, include statistical analyses that support your findings.

- Findings: Summarize the key findings of your research, highlighting significant results and trends.

Discussion

When writing a dissertation, the discussion section is where you interpret and analyze the results presented in the previous section. Here, you connect your findings to your research questions, objectives, and the existing literature. In the discussion section:

- Interpret Findings: Explain the meaning and implications of your results. Discuss how they relate to your research questions or hypotheses.

- Compare to Existing Literature: Compare your findings to previous research and theories in your field. Highlight similarities, differences, or contributions to the existing knowledge.

- Limitations: Acknowledge any limitations of your study, such as sample size, data collection methods, or potential bias.

- Future Directions: Suggest areas for future research based on your findings and limitations.

Conclusion

The conclusion section is the culmination of your dissertation, where you bring together all the key points and findings, much like a well-crafted dissertation proposal, to provide a final, overarching assessment of your research. In the conclusion:

- Summarize Findings: Recap the main findings and results of your study.

- Address Research Questions: Reiterate how your research has addressed the primary research questions or objectives.

- Theoretical and Practical Implications: Discuss the broader implications of your research, both in terms of theoretical contributions to your field and practical applications.

- Recommendations: Offer any recommendations for future research or practical actions that can be drawn from your study.

- Closing Thoughts: Provide a concise, thought-provoking statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

Bibliography

The Bibliography (or References) section is a comprehensive list of all the sources you cited and referenced throughout your dissertation. This section follows a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, and Chicago. By this point, you should be well-versed in knowing how to cite an essay APA or a style prescribed by your institution or field. The bibliography section includes:

- Books: List books in alphabetical order by the author's last name.

- Journal Articles: Include journal articles with complete citation details.

- Online Sources: Cite online sources, websites, and electronic documents with proper URLs or DOIs.

- Other References: Include any other sources, such as reports, conference proceedings, or interviews, following the appropriate citation style

Appendices

The Appendices section is where you include supplementary material that supports or enhances your dissertation but is not part of the main body of the text. Appendices may include:

- Raw Data: Any large datasets, surveys, or interview transcripts that were used in your research process.

- Additional Figures and Tables: Extra visual elements that provide context or details beyond what is included in the main text.

- Questionnaires: Copies of questionnaires or survey instruments used in your research.

- Technical Details: Any technical documents, code, or algorithms that are relevant to your research.

Proofreading and Editing

Proofreading and editing are crucial steps in the dissertation-writing process that ensure the clarity, coherence, https://myidlyrics.com and correctness of your work. In this phase:

- Grammar and Spelling: Carefully review your dissertation for grammar and spelling errors and correct them systematically.

- Style and Formatting: Ensure consistent formatting throughout your dissertation, following the required style guide (e.g., APA, MLA).

- Clarity and Coherence: Check that your arguments flow logically, with clear transitions between sections and paragraphs.

- Citation Accuracy: Ensure the accuracy and consistency of your citations and references, whether you have referred to other dissertation examples or not.

- Content Review: Examine the content for accuracy, relevance, and completeness, making necessary revisions.

Defending Your Dissertation

The dissertation defense is the final step in completing your doctoral journey. During this process:

- Oral Presentation: Typically, you will present your research findings and dissertation to a committee of experts in your field.

- Q&A Session: The committee will ask questions about your research, methodology chapter, findings, and their implications.

- Defense of Arguments: You will defend your arguments, interpretations, and conclusions.

- Discussion and Feedback: Expect a discussion with the committee about your research, including strengths, weaknesses, and potential areas for improvement.

- Outcome: Following the defense, the committee will decide whether to accept your dissertation as is, accept it with revisions, or reject it.

How to write dissertation

Dissertation introduction, conclusion and abstract

Published

2 years agoon

November 17, 2023Dissertation introduction, conclusion and abstract

But why?

Firstly, writing retrospectively means that your dissertation introduction and conclusion will ‘match’ and your ideas will all be tied up nicely.

Secondly, http://itgamer.ru/community/profile/senaida05627001/ it’s time-saving. If you write your introduction before anything else, it’s likely your ideas will evolve and morph as your dissertation develops. And then you’ll just have to go back and edit or totally re-write your introduction again.

Thirdly, it will ensure that the abstract accurately contains all the information it needs for the reader to get a good overall picture about what you have actually done.

So as you can see, it will make your life much easier if you plan to write your introduction, conclusion, and abstract last when planning out your dissertation structure.

In this guide, we’ll break down the structure of a dissertation and run through each of these chapters in detail so you’re well equipped to write your own. We’ve also identified some common mistakes often made by students in their writing so that you can steer clear of them in your work.

The Introduction

Getting started

-

Provide preliminary background information that puts your research in context

-

Clarify the focus of your study

-

Point out the value of your research(including secondary research)

-

Specify your specific research aims and objectives

check out this blog post about How to write dissertation https://www.32acp.com/index.php/community/profile/geraldinejasper/ .

There are opportunities to combine these sections to best suit your needs. There are also opportunities to add in features that go beyond these four points. For example, some students like to add in their research questions in their dissertation introduction so that the reader is not only exposed to the aims and objectives but also has a concrete framework for where the research is headed. Other students might save the research methods until the end of the literature review/beginning of the methodology.

In terms of length, there is no rule about how long a dissertation introduction needs to be, as it is going to depend on the length of the total dissertation. Generally, however, if you aim for a length between 5-7% of the total, this is likely to be acceptable.

Your introduction must include sub-sections with appropriate headings/subheadings and should highlight some of the key references that you plan to use in the main study. This demonstrates another reason why writing a dissertation introduction last is beneficial. As you will have already written the literature review, the most prominent authors will already be evident and you can showcase this research to the best of your ability.

The background section

The reader needs to know why your research is worth doing. You can do this successfully by identifying the gap in the research and the problem that needs addressing. One common mistake made by students is to justify their research by stating that the topic is interesting to them. While this is certainly an important element to any research project, and to the sanity of the researcher, the writing in the dissertation needs to go beyond ‘interesting’ to why there is a particular need for this research. This can be done by providing a background section.

You are going to want to begin outlining your background section by identifying crucial pieces of your topic that the reader needs to know from the outset. A good starting point might be to write down a list of the top 5-7 readings/authors that you found most influential (and as demonstrated in your literature review). Once you have identified these, write some brief notes as to why they were so influential and how they fit together in relation to your overall topic.

You may also want to think about what key terminology is paramount to the reader being able to understand your dissertation. While you may have a glossary or list of abbreviations included in your dissertation, your background section offers some opportunity for you to highlight two or three essential terms.

When reading a background section, there are two common mistakes that are most evident in student writing, either too little is written or far too much! In writing the background information, one to two pages is plenty. You need to be able to arrive at your research focus quite quickly and only provide the basic information that allows your reader to appreciate your research in context.

The research focus

It is essential that you are able to clarify the area(s) you intend to research and you must explain why you have done this research in the first place. One key point to remember is that your research focus must link to the background information that you have provided above. While you might write the sections on different days or even different months, it all has to look like one continuous flow. Make sure that you employ transitional phrases to ensure that the reader knows how the sections are linked to each other.

The research focus leads into the value, aims and objectives of your research, so you might want to think of it as the tie between what has already been done and the direction your research is going. Again, you want to ease the reader into your topic, so stating something like “my research focus is…” in the first line of your section might come across overly harsh. Instead, you might consider introducing the main focus, explaining why research in your area is important, and the overall importance of the research field. This should set you up well to present your aims and objectives.

The value of your research

The biggest mistake that students make when structuring their dissertation is simply not including this sub-section. The concept of ‘adding value’ does not have to be some significant advancement in the research that offers profound contributions to the field, but you do have to take one to two paragraphs to clearly and unequivocally state the worth of your work.

There are many possible ways to answer the question about the value of your research. You might suggest that the area/topic you have picked to research lacks critical investigation. You might be looking at the area/topic from a different angle and this could also be seen as adding value. In some cases, it may be that your research is somewhat urgent (e.g. medical issues) and value can be added in this way.

Whatever reason you come up with to address the value added question, make sure that somewhere in this section you directly state the importance or added value of the research.

The research and the objectives

Typically, a research project has an overall aim. Again, this needs to be clearly stated in a direct way. The objectives generally stem from the overall aim and explain how that aim will be met. They are often organised numerically or in bullet point form and are terse statements that are clear and identifiable.

There are four things you need to remember when creating research objectives. These are:

-

Appropriateness (each objective is clearly related to what you want to study)

-

Distinctness (each objective is focused and incrementally assists in achieving the overall research aim)

-

Clarity (each objective avoids ambiguity)

-

Being achievable (each objective is realistic and can be completed within a reasonable timescale)

-

Starting each objective with a key word (e.g. identify, assess, evaluate, explore, examine, investigate, determine, etc.)

-

Beginning with a simple objective to help set the scene in the study

-

Finding a good numerical balance – usually two is too few and six is too many. Aim for approximately 3-5 objectives

Remember that you must address these research objectives in your research. You cannot simply mention them in your dissertation introduction and then forget about them. Just like any other part of the dissertation, this section must be referenced in the findings and discussion – as well as in the conclusion.

This section has offered the basic sections of a dissertation introduction chapter. There are additional bits and pieces that you may choose to add. The research questions have already been highlighted as one option; an outline of the structure of the entire dissertation may be another example of information you might like to include.

As long as your dissertation introduction is organised and clear, you are well on the way to writing success with this chapter.

The Conclusion

Getting started

It is your job at this point to make one last push to the finish to create a cohesive and organised final chapter. If your concluding chapter is unstructured or some sort of ill-disciplined rambling, the person marking your work might be left with the impression that you lacked the appropriate skills for writing or that you lost interest in your own work.

To avoid these pitfalls and fully understand how to write a dissertation conclusion, you will need to know what is expected of you and what you need to include.

There are three parts (at a minimum) that need to exist within your dissertation conclusion. These include:

-

Research objectives – a summary of your findings and the resulting conclusions

-

Recommendations

-

Contributions to knowledge

Furthermore, just like any other chapter in your dissertation, your conclusion must begin with an introduction (usually very short at about a paragraph in length). This paragraph typically explains the organisation of the content, reminds the reader of your research aims/objectives, and provides a brief statement of what you are about to do.

The length of a dissertation conclusion varies with the length of the overall project, but similar to a dissertation introduction, a 5-7% of the total word count estimate should be acceptable.

Research objectives

These are:

1. As a result of the completion of the literature review, along with the empirical research that you completed, what did you find out in relation to your personal research objectives?2. What conclusions have you come to?

A common mistake by students when addressing these questions is to again go into the analysis of the data collection and findings. This is not necessary, as the reader has likely just finished reading your discussion chapter and does not need to go through it all again. This section is not about persuading, you are simply informing the reader of the summary of your findings.

Before you begin writing, it may be helpful to list out your research objectives and then brainstorm a couple of bullet points from your data findings/discussion where you really think your research has met the objective. This will allow you to create a mini-outline and avoid the ‘rambling’ pitfall described above.

Recommendations

There are two types of recommendations you can make. The first is to make a recommendation that is specific to the evidence of your study, the second is to make recommendations for future research. While certain recommendations will be specific to your data, there are always a few that seem to appear consistently throughout student work. These tend to include things like a larger sample size, different context, increased longitudinal time frame, etc. If you get to this point and feel you need to add words to your dissertation, this is an easy place to do so – just be cautious that making recommendations that have little or no obvious link to the research conclusions are not beneficial.

A good recommendations section will link to previous conclusions, and since this section was ultimately linked to your research aims and objectives, the recommendations section then completes the package.

Contributions to knowledge

Your main contribution to knowledge likely exists within your empirical work (though in a few select cases it might be drawn from the literature review). Implicit in this section is the notion that you are required to make an original contribution to research, and you are, in fact, telling the reader what makes your research study unique. In order to achieve this, you need to explicitly tell the reader what makes your research special.

There are many ways to do this, but perhaps the most common is to identify what other researchers have done and how your work builds upon theirs. It may also be helpful to specify the gap in the research (which you would have identified either in your dissertation introduction or literature review) and how your research has contributed to ‘filling the gap.’

Another obvious way that you can demonstrate that you have made a contribution to knowledge is to highlight the publications that you have contributed to the field (if any). So, for example, if you have published a chapter of your dissertation in a journal or you have given a conference presentation and have conference proceedings, you could highlight these as examples of how you are making this contribution.

In summing up this section, remember that a dissertation conclusion is your last opportunity to tell the reader what you want them to remember. The chapter needs to be comprehensive and must include multiple sub-sections.

Ensure that you refresh the reader’s memory about your research objectives, formazione.geqmedia.it tell the reader how you have met your research objectives, provide clear recommendations for future researchers and demonstrate that you have made a contribution to knowledge. If there is time and/or space, you might want to consider a limitations or self-reflection section.

The Abstract

A good abstract will contain the following elements:

-

A statement of the problem or issue that you are investigating – including why research on this topic is needed

-

The research methods used

-

The main results/findings

-

The main conclusions and recommendations

Different institutions often have different guidelines for writing the abstract, so it is best to check with your department prior to beginning.

When you are writing the abstract, you must find the balance between too much information and not enough. You want the reader to be able to review the abstract and get a general overall sense of what you have done.

As you write, you may want to keep the following questions in mind:

1. Is the focus of my research identified and clear?

2. Have I presented my rationale behind this study?

3. Is how I conducted my research evident?

4. Have I provided a summary of my main findings/results?

5. Have I included my main conclusions and recommendations?

In some instances, you may also be asked to include a few keywords. Ensure that your keywords are specifically related to your research. You are better off staying away from generic terms like ‘education’ or ‘science’ and instead provide a more specific focus on what you have actually done with terms like ‘e-learning’ or ‘biomechanics’.

Finally, you want to avoid having too many acronyms in your abstract. The abstract needs to appeal to a wide audience, and so making it understandable to this wider audience is absolutely essential to your success.

Ultimately, writing a good abstract is the same as writing a good dissertation; you must present a logical and organised synopsis that demonstrates what your research has achieved. With such a goal in mind, you can now successfully proceed with your abstract!

Many students also choose to make the necessary efforts to ensure that their chapter is ready for submission by applying an edit to their finished work. It is always beneficial to have a fresh set of eyes have a read of your chapter to make sure that you have not omitted any vital points and that it is error free.

How to write dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Step-by-Step Guide

Published

2 years agoon

November 17, 2023How to Write a Dissertation: Step-by-Step Guide

- Doctoral students write and defend dissertations to earn their degrees.

- Most dissertations range from 100-300 pages, depending on the field.

- Taking a step-by-step approach can help students write their dissertations.

Whether you're considering a doctoral program or you recently passed your comprehensive exams, you've probably wondered how to write a dissertation. Researching, writing, and defending a dissertation represents a major step in earning a doctorate.

But what is a dissertation exactly? A dissertation is an original work of scholarship that contributes to the field. Doctoral candidates often spend 1-3 years working on their dissertations. And many dissertations top 200 or more pages.

Starting the process on the right foot can help you complete a successful dissertation. Breaking down the process into steps may also make it easier to finish your dissertation.

How to Write a Dissertation in 12 Steps

A dissertation demonstrates mastery in a subject. But how do you write a dissertation? Here are 12 steps to successfully complete a dissertation.

Choose a Topic

Choose a Topic

Read also How to write dissertation https://kursy.certyfikatpolski.org/blog/index.php?entryid=17564 .

It sounds like an easy step, but choosing a topic will play an enormous role in the success of your dissertation. In some fields, your dissertation advisor estesparkrentals.com will recommend a topic. In other fields, you'll develop a topic on your own.

Read recent work in your field to identify areas for additional scholarship. Look for holes in the literature or questions that remain unanswered.

After coming up with a few areas for research or questions, carefully consider what's feasible with your resources. Talk to your faculty advisor about your ideas and incorporate their feedback.

Conduct Preliminary Research

Conduct Preliminary Research

Before starting a dissertation, you'll need to conduct research. Depending on your field, that might mean visiting archives, reviewing scholarly literature, or running lab tests.

Use your preliminary research to hone your question and topic. Take lots of notes, particularly on areas where you can expand your research.

Read Secondary Literature

Read Secondary Literature

A dissertation demonstrates your mastery of the field. That means you'll need to read a large amount of scholarship on your topic. Dissertations typically include a literature review section or chapter.

Create a list of books, articles, and other scholarly works early in the process, and continue to add to your list. Refer to the works cited to identify key literature. And take detailed notes to make the writing process easier.

Write a Research Proposal

Write a Research Proposal

In most doctoral programs, you'll need to write and defend a research proposal before starting your dissertation.

The length and format of your proposal depend on your field. In many fields, the proposal will run 10-20 pages and include a detailed discussion of the research topic, methodology, and secondary literature.

Your faculty advisor will provide valuable feedback on turning your proposal into a dissertation.

Research, Research, Research

Research, Research, Research

Doctoral dissertations make an original contribution to the field, and your research will be the basis of that contribution.

The form your research takes will depend on your academic discipline. In computer science, you might analyze a complex dataset to understand machine learning. In English, you might read the unpublished papers of a poet or author. In psychology, you might design a study to test stress responses. And in education, you might create surveys to measure student experiences.

Work closely with your faculty advisor as you conduct research. Your advisor can often point you toward useful resources or recommend areas for further exploration.

Look for Dissertation Examples

Look for Dissertation Examples

Writing a dissertation can feel overwhelming. Most graduate students have written seminar papers or a master's thesis. But a dissertation is essentially like writing a book.

Looking at examples of dissertations can help you set realistic expectations and understand what your discipline wants in a successful dissertation. Ask your advisor if the department has recent dissertation examples. Or use a resource like ProQuest Dissertations to find examples.

Doctoral candidates read a lot of monographs and articles, but they often do not read dissertations. Reading polished scholarly work, particularly critical scholarship in your field, can give you an unrealistic standard for writing a dissertation.

Write Your Body Chapters

Write Your Body Chapters

By the time you sit down to write your dissertation, you've already accomplished a great deal. You've chosen a topic, defended your proposal, and conducted research. Now it's time to organize your work into chapters.

As with research, the format of your dissertation depends on your field. Your department will likely provide dissertation guidelines to structure your work. In many disciplines, dissertations include chapters on the literature review, methodology, and results. In other disciplines, each chapter functions like an article that builds to your overall argument.

Start with the chapter you feel most confident in writing. Expand on the literature review in your proposal to provide an overview of the field. Describe your research process and analyze the results.

Meet With Your Advisor

Meet With Your Advisor

Throughout the dissertation process, you should meet regularly with your advisor. As you write chapters, send them to your advisor for feedback. Your advisor can help identify issues and suggest ways to strengthen your dissertation.

Staying in close communication with your advisor will also boost your confidence for your dissertation defense. Consider sharing material with other members of your committee as well.

Write Your Introduction and Conclusion

Write Your Introduction and Conclusion

It seems counterintuitive, stellarhaat.com but it's a good idea to write your introduction and conclusion last. Your introduction should describe the scope of your project and your intervention in the field.

Many doctoral candidates find it useful to return to their dissertation proposal to write the introduction. If your project evolved significantly, you will need to reframe the introduction. Make sure you provide background information to set the scene for your dissertation. And preview your methodology, research aims, and results.

The conclusion is often the shortest section. In your conclusion, sum up what you've demonstrated, and explain how your dissertation contributes to the field.

Edit Your Draft

Edit Your Draft

You've completed a draft of your dissertation. Now, it's time to edit that draft.

For some doctoral candidates, the editing process can feel more challenging than researching or writing the dissertation. Most dissertations run a minimum of 100-200 pages, with some hitting 300 pages or more.

When editing your dissertation, break it down chapter by chapter. Go beyond grammar and spelling to make sure you communicate clearly and efficiently. Identify repetitive areas and shore up weaknesses in your argument.

Incorporate Feedback

Incorporate Feedback

Writing a dissertation can feel very isolating. You're focused on one topic for months or years, and you're often working alone. But feedback will strengthen your dissertation.

You will receive feedback as you write your dissertation, both from your advisor and other committee members. In many departments, doctoral candidates also participate in peer review groups to provide feedback.

Outside readers will note confusing sections and recommend changes. Make sure you incorporate the feedback throughout the writing and editing process.

Defend Your Dissertation

Defend Your Dissertation

Congratulations — you made it to the dissertation defense! Typically, your advisor will not let you schedule the defense unless they believe you will pass. So consider the defense a culmination of your dissertation process rather than a high-stakes examination.

The format of your defense depends on the department. In some fields, you'll present your research. In other fields, the defense will consist of an in-depth discussion with your committee.

Walk into your defense with confidence. You're now an expert in your topic. Answer questions concisely and address any weaknesses in your study. Once you pass the defense, you'll earn your doctorate.

Writing a dissertation isn't easy — only around 55,000 students earned a Ph.D. in 2020, according to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. However, it is possible to successfully complete a dissertation by breaking down the process into smaller steps.

Frequently Asked Questions About Dissertations

What is a dissertation?

A dissertation is a substantial research project that contributes to your field of study. Graduate students write a dissertation to earn their doctorate.

The format and content of a dissertation vary widely depending on the academic discipline. Doctoral candidates work closely with their faculty advisor to complete and defend the dissertation, a process that typically takes 1-3 years.

How long is a dissertation?

The length of a dissertation varies by field. Harvard's graduate school says most dissertations fall between 100-300 pages.

Doctoral candidate Marcus Beck analyzed the length of University of Minnesota dissertations by discipline and found that history produces the longest dissertations, with an average of nearly 300 pages, while mathematics produces the shortest dissertations at just under 100 pages.

What's the difference between a dissertation vs. a thesis?

Dissertations and theses demonstrate academic mastery at different levels. In U.S. graduate education, master's students typically write theses, while doctoral students write dissertations. The terms are reversed in the British system.

In the U.S., a dissertation is longer, more in-depth, and based on more research than a thesis. Doctoral candidates write a dissertation as the culminating research project of their degree. Undergraduates and master's students may write shorter theses as part of their programs.

HIV E Perda De Peso Causas, Tratamentos, É Sempre Seguro

Os 16 Melhores Cuidados Com A Pele

A Jornada Pessoal De Kim Com Hepatite C

Trending

-

Business2 years ago

Exploring Costa Brava: A Guide to Discovering the Perfect Vacation Rental

-

Uncategorized25 years ago

SLOT2D Bocoran HK – Prediksi HK – Angka Main HK – Prediksi Togel Hongkong

-

Business2 years ago

Canine Hydrotherapy Pools: The Ultimate Guide for Canine Wellness

-

Business2 years ago

Selecting the Excellent Baby Clothes: A Complete Guide

-

Business2 years ago

The Benefits of Dog Hydrotherapy: A Complete Guide

-

Business2 years ago

Steps to Take Instantly When Your Credit Card is Stolen

-

Business2 years ago

The Benefits of Dog Hydrotherapy: A Comprehensive Guide

-

Business2 years ago

Dog Hydrotherapy Swimming pools: The Ultimate Guide for Canine Wellness