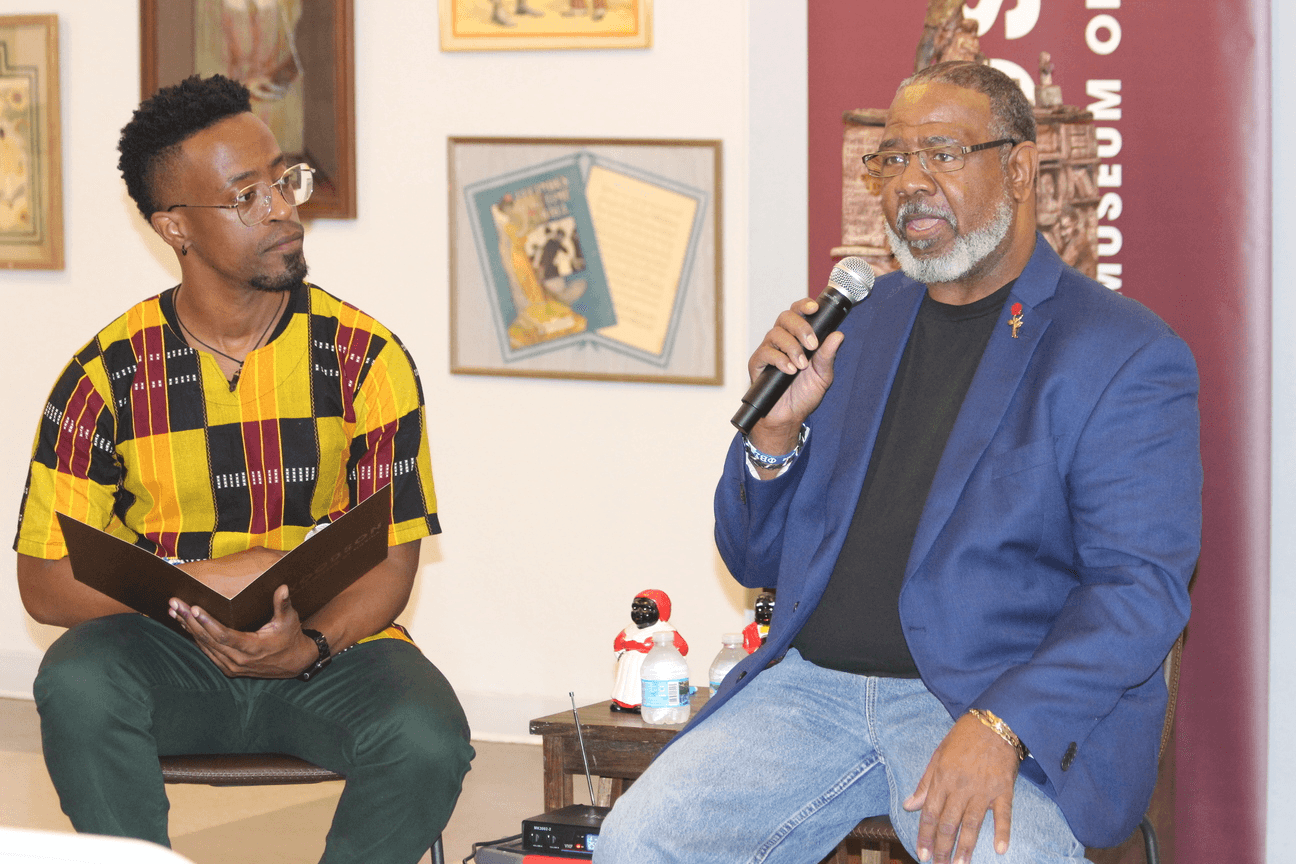

By J.A. Jones, Staff Writer

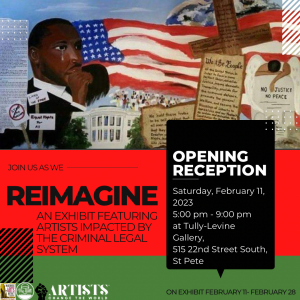

ST. PETERSBURG – The liberating force of creativity is on display this month at the Tully-Levine ArtsXChange, as the Warehouse Arts District Association (WADA) presents REIMAGINE, an exhibition of Black artists impacted by the criminal legal system.

A collaboration with The Well for Life and the Green Book of Tampa Bay, artists Alfred Cleveland, Catherine E. Weaver, Anthony Williams, Christopher Williams, F. Axom, Jabaar Edmonds, and David Lee Watson share works that combine storytelling, dream-weaving, healing, and envisioning new worlds and futures.

On view through the end of February, the show begins with an opening reception from 5 pm to 9 pm on Saturday, February 11, during Second Saturday ArtWalk, and features local and national artists.

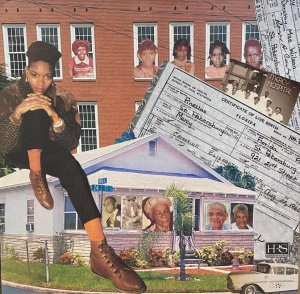

Catherine Weaver, a native of St. Pete and founder of Uniquely Original Art Studio, shared that her own art practice started when she was nine years old. “The first job I ever had was as an arts and craft assistant at Barclay Park recreation center at the age of 14.”

The self-taught artist, whose work has been seen on the Black Lives Matter mural in front The Woodson, comes from a family with three-generation of entrepreneurs. “The building where Original Art Studio is located has been family owned and operated since 1947 when it was first built by my grandfather,” Weaver has shared.

Catherine Weaver, Artist

“I am a visual artist, but I also write poetry…on social justice issues and personal life-altering experiences, such as gentrification, racism, slavery, domestic violence, and homelessness,” themes which have also inspired several artworks.

Weaver says her visual work often reflects African-American History, family, and community – and she is most inspired by the beauty of African-American women, “our strength, culture and individual style.”

Al Cleveland, a 53-year-old native of Queens, NY, who now resides in Cleveland, Ohio, remembers his kindergarten teacher calling his mother to the school and telling her she had an artist on her hands. His mother immediately went out and bought him an easel and paints, “and gave me a space in the basement to mess things up.”

Coming of age in NYC’s hip-hop culture, he became a well-known graffiti artist called “Krak 5” and developed a unique set of floating bubble letters that became came to be known as “Flinstones.” His style was copied by others, and soon he was commissioned by then, up-and-coming rapper LL Cool J to paint a mural on his bedroom wall.

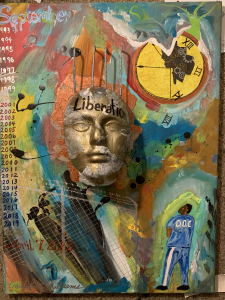

Al Cleveland, Artist

While he was rejected by the gallery art scene, Cleveland began painting murals that “became part of the everyday landscape for Queens, New Yorkers.” Eventually, the graffiti movement slowed down, and Cleveland’s life took a turn when he was incarcerated. But he says, the experience eventually inspired in him to a new revelation on his art abilities — and his future goals. “Seeing people return again and again, I prayed to never come back to prison again.”

Cleveland said he decided to take art seriously and develop the skills he had, hoping to begin a career in art after his release. The lack of pencils meant he could only draw with a pen — so he began doing portraits with dots. “This set the stage for an art technique I would use for years to come, stippling. This became a therapeutic form of art as I would lose myself in these drawings and realize five hours later that I was drawing and that much time has passed. Rather than emotional, this form of art developed in me patience and focus and became a spiritual experience.”

The artist was released from prison in 2020, after serving 26 years of a wrongful conviction; today he uses ‘live wood’ as his canvas: “Wood is very inspiring to me, it breathes and is alive. There’s a connection between it and us, and we are codependent on each other for life, for air!”

Brother Christopher and Anthony Williams were also born in Queens, New York, but relocated to St. Petersburg while they were still young.

Christopher served 28 years before being released. “I was about three or four years old when I started to place shapes and colors together on paper to create my vision and thought.”

Christopher Williams, Artist

But while he was locked up, Williams said a lack of formal art classes meant doing “piece art” with the leftover pencils he could find. He’d send that artwork home by mail but didn’t get to do any of the richly imaginative and afrofuturistic paintings he’s now doing.

Combining visions of space, spirituality, and often 3-D elements on canvas, Williams says that when was a child he loved mixing colors, and would melt his crayons on the radiator to create blended wax he could create into “sculptures.”

He dabbled in “comic book” art while at Lakewood High School but acknowledged that the cost of really pursuing art and lack of guidance were barriers.

“In your teenage years, if nobody’s really pushing on you to be creative, you’re not going to create, unless you really push for it. You got to have the funds to have the art; the school’s only going to do so much for you,” he said, noting that most school programs only notice the extremely gifted youth.

He believes more free art classes in recreation centers and parks are needed and would draw young people and budding artists who would benefit from guidance.

His younger brother Anthony was incarcerated for a much shorter amount of time and reiterated missing the ability to practice his art while incarcerated. His pieces were created during the eight-year span since he returned home.

Anthony Williams, Artist

“I’ve been an artist my entire life; since I was a child, I would pick up a pencil and draw — just for my own entertainment, and my friends and family,” Anthony shared. “My motivation generally is what I feel.” Sometimes, he noted, the idea for a piece of artwork will be germinating in his head for years before he actually starts putting it on paper.

He finds inspiration in “everyday things – simple stuff; kids laughing; children being children without a care in the world. I like people-watching. I enjoy community.”

Like his brother, he works in a variety of mediums, with fashion and music being among the arts he practices. “My mother blessed us by playing a lot of music around us when I was when we kids, taught me to read very early; let me be imaginative, let me run free, make my own mythology, study whatever I

On Feb. 22, at 7 pm, there will be a panel discussion featuring some of the visiting artists, community advocates, and family members who have also been impacted by the criminal legal system.

The exhibit is shown at the Tully-Levine Gallery at the ArtsXchange Plaza located on the historic Deuces corridor, 515 22nd Street South. Visit the website at www.wadastpete.org.

Post Views:

2,874